Fac bene nec dubitans

(Do well and doubt not)

– Blakiston Family Motto

At precisely 12:00 hours (Zulu time) I step from the glare and bustle of Picadilly into the cool, hushed realm of the Dragoons and Lancers Club. Instantly I am transported from a London summer’s day to an older world of reverence, order, elegance, tradition and timelessness. As the heavy door closes behind me, the roar of the city fades to a murmur. A hefty clock ticks away the ponderous seconds above the footman’s counter.

The footman, immaculate in a morning coat with sharp creases and shimmering brass buttons, has the air and bearing of a soldier. He asks my name and who I am here to see. I reply that I am meeting my cousin, Colonel Charles Cubitt-Mann, and I have been ordered for 12:15.

“You are a little early, sir,” he replies. “Would you care to wait in the main hall?”

He leads me into a grand, open space with floor tiles in the black and white Nelson Checker, Doric columns, and several large leather sofas. I take a seat and stare, unbelieving, at my surroundings. Sunlight falls in an ivory wash across the tiles. A portrait of a member of the royal family (the regiment’s patron), resplendent in a blue gown and wearing a diamond tiara, looks warmly down at me.

The walls are covered with military memorabilia: medals from countless conflicts, gleaming swords, pistols, shields and regimental colours. A grand staircase of marble and polished wood curves upwards behind me to the first floor.

My cousin arrives at precisely 12:15. After a lifetime in the military, he knows the importance of punctuality. He is dressed in a blue, three-piece suit. I am wearing trousers, a perfectly pressed shirt with a tie, and a tweed jacket. I have deliberately chosen my attire out of respect for the club, for my cousin, and for the dignity of the military traditions the club encapsulates.

Normally, I would play the rough colonial, unmoved by notions of traditions and preconceived ideas about respectability. But not today. I feel very privileged to have been invited to dine at the Dragoons and Lancers Club, and my clothes — however impractical for a hot London day — reflect my understanding of the setting, steeped as it is in centuries of tradition and respect.

We climb the staircase to the club’s first floor. From the high-ceilinged corridor, oak-panelled doors lead to discreet rooms and chambers, each one bedecked with portraits of military men and scenes from great moments in military history: the retreat from Kabul, the Battle of Plassey, Captain Oats leaving the tent in an Antarctic blizzard: “…I may be some time.”

Pride of place in one room goes to a polo cup that had once been contested every year in the high valley of Gilgit in what is now the Northwest Frontier Province of Pakistan, a place Linda and I have visited several times.

The portraits and paintings, busts and bayonets, medals and manuscripts are more than mere decorations; they are tributes to individuals who have shaped history. Each artefact is a tangible connection to the past, to stories of bravery, action and sacrifice.

These moments of triumph and tragedy seem to exist as both a record of deeds and as a reminder of the complexities of history and the stories entwined with it: art and artefact merging to create a tapestry of military history.

As we walk through the halls, I feel a growing sense of connection with the men who have inhabited these spaces. I imagine stories being told over postprandial glasses of port, the cigars drawing, the leather chairs creaking, the click of snooker balls, valets and batmen moving obsequiously from group to group.

The atmosphere is rich with respect for the past and recognition of the sacrifices made by those who have walked these rooms before. Despite the years or perhaps centuries that separate us, I feel an undeniable connection to these powerful figures who gaze from gilt frames, their faces imbued with the weight of their experiences and achievements.

Standing before these portraits, I am not just an observer: I am part of a silent conversation stretching across time. It feels as if their stories, their struggles and their triumphs are being quietly communicated, each one a reminder of the legacy of those who serve in the armed forces.

I reflect that in another time, in another life, I too might have been part of this legacy, this ongoing story. Perhaps if my ancestors had not left England for new lives in the southern colonies I might have followed the family tradition of soldiering, to do well and doubt not.

Perhaps I would have joined this world of duty, honour and camaraderie: a parallel existence where I wore a uniform, faced the challenges and earned a place among these strong figures honoured on the walls of the Dragoons and Lancers Club.

But time is linear and my story does not include the military. Instead, I stand here a visitor, enthralled and fascinated by these artefacts and stories but completely separate from them.

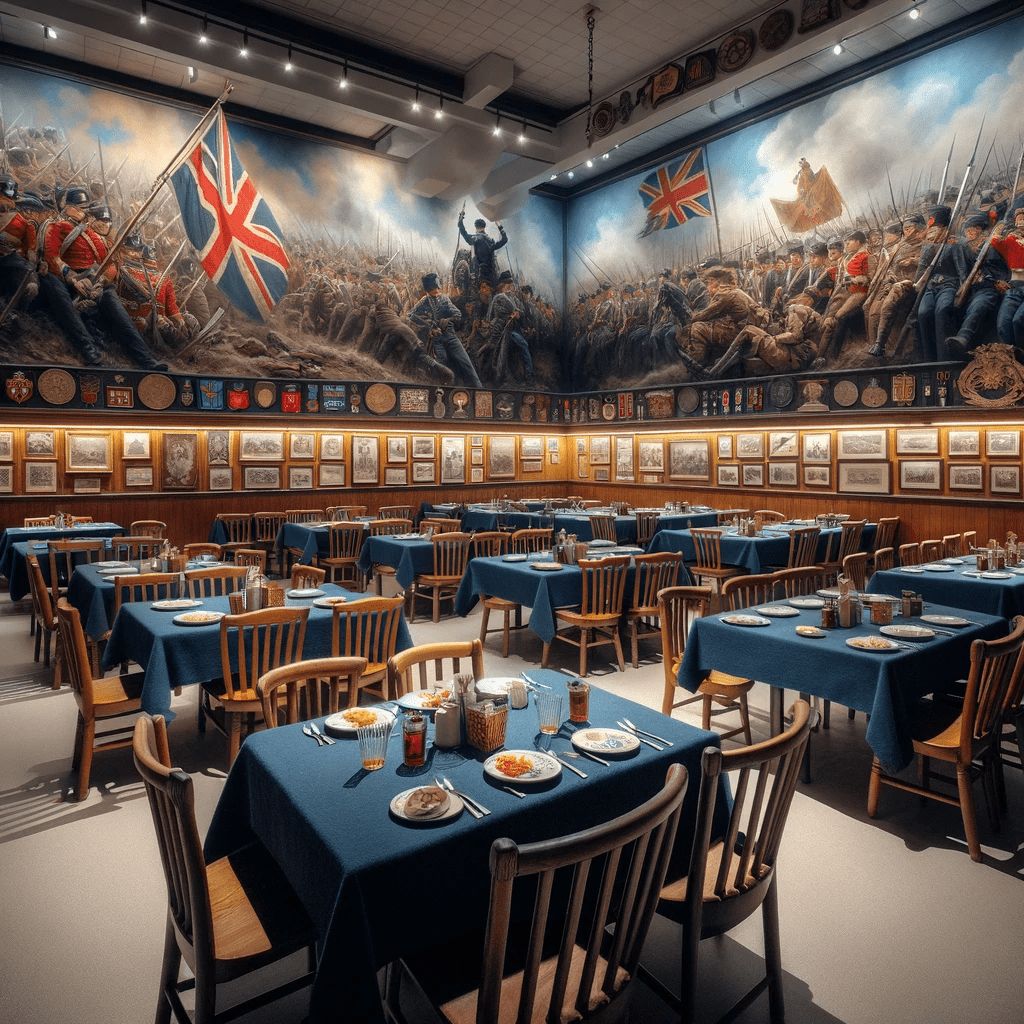

We descend a set of creaking back stairs to the dining room and re-enter the modern realm. The room is empty save for a group of four, very well-spoken military wives lunching over glasses of bubbly. This sparse occupancy is a sudden jarring reminder and a profound realisation of the changing times. I’d expected a room crowded with soldiers of all ages, with busy servicemen moving with military precision between tables loaded with food and drinks: whiskey and sodas, an occasional pint of beer, mess dishes of stroganoff and curry.

But there is just my cousin and I along with the four old ladies who are discussing some tennis match in an upcoming tournament at Queens Club Gardens. After the vibrant history of the rooms upstairs, the quietness of the dining room is a stark reminder of the relevance of clubs like this in the modern world. These institutions, once the heart of military camaraderie and tradition, are now facing a decline in patronage, particularly among the younger generation of military personnel.

It is a reminder that no matter how strong traditions may be, they evolve, grow strong and sometimes fade as new ways and changing priorities take hold.

We order drinks and lunch: a pint of Fuller’s London Pride bitter for me, a chardonnay for Charles, and toasted sandwiches for two. Charles asks the waiter if he is a former serviceman. He replies that both he and his assistant are civilians. He knows virtually nothing about the club; to him, this is just a job. Nothing lasts forever. All things pass.

Nevertheless, it is pleasant to sit here in these quiet, convivial surroundings. I have a busy afternoon planned but for now, I am happy to sit and listen to the Colonel talk about his time in the army and his deployments to Borneo, Northern Ireland and West Germany.

With our lunch finished, we prepare to leave. My plan is to walk back to Green Park station and catch the Underground to Oxford Street to buy a birthday present for Linda. From there, I have to collect all of our gear from our friend’s house in Notting Hill and take it to a hotel in King’s Cross where my family are to rendezvous at 19:00.

But as any commander will tell you, no plan survives first contact with the enemy.

“Right Ferg,” says Charles. He pronounces it “FARRG”; always has done. “I have two tickets to go aboard HMS Belfast if you’re interested.”

Of course I’m interested. HMS Belfast, a pocket battleship moored on the Thames near Tower Bridge, has been on my bucket list for years. But with so many things to get done this afternoon, I initially refuse the invitation. On the other hand, if I hurry I can make it to Oxford Street, do my shopping, meet Charles on the hard at Queens Walk at six bells in the afternoon watch, and go aboard in good order.

I say: “Fuck it! I’ll do my jobs then meet you beside the warship at six bells.”

It feels liberating, almost rebellious to embrace the prospect of an unplanned adventure and jettison my carefully worked-out plans.

Leaving Charles to finish his wine, I step from the club into the glare of the afternoon sun, now beating like an artillery barrage on Picadilly’s grand facades. Platoons of afternoon commutes are taking cover amid the shade of Green Park. Echelons of black taxis and red buses debouche along the street, intent on their acquired targets.

I turn and look up at the flags flying above the door of the Dragoons and Lancers Club, still resplendent and dignified despite the passing years and changing times. Just like the flags that weather the seasons but never lose their grandeur, the Dragoons and Lancers Club remains a testament to the enduring spirit and tenacity of those who served.

My visit to the club has been a bridge between past and present, a journey through traditions that continue to shape memory and identity. I feel a sense of solemn pride at having been given a glimpse of it all, even if just for a moment.

As I descend into the humid fug of the Underground, the anticipation of stepping onto the deck of HMS Belfast — another splendid and dignified artefact of history — intertwines with the respect and reflection I carry from the club. But the details of that operation are another story.

Author’s Note: For security reasons, I have changed the name of both the club where we met and that of my cousin. I also did not take any photographs, partly out of respect for the institution and partly for security reasons. The images used for this post are either generated by AI (I use DALL.E) or stock photographs from the internet. All other details are exactly as I remember them.