I am there now, as I write; I fancy that I can see the downs, the huts, the plain, and the river-bed – that torrent pathway of desolation, with its distant roar of waters.

- Samuel Butler, Erewhon.

Trafalgar Square at dawn. The square stretches out empty before me, its usual hustle momentarily paused. London, my favourite city in the world, feels like it belongs solely to me at this hour. A few pigeons are gathered for their morning ablutions in the pools left by an overnight shower. Early commuters are getting their coffees at Pret-a-Manger on the corner of Northumberland Ave. The beggars beneath the trees outside Waterstones are still asleep on their cardboard charpois.

The statue of King Charles I stares resolutely down Whitehall. Mounted on a stallion, the king is bareheaded, wearing armour and the Order of the Garter. The statue is often lost in the crowd of tourists and the shadows of lions and fountains. But at this hour, it commands the space with a quiet dignity. The rising sun casts a soft glow on his bronzed figure, highlighting the intricate details of his royal garb.

I can feel the palpable weight of history in this place. Here, alone in the heart of London, I am surrounded by the echoes of an empire whose spokes once spread out across the globe. And this statue was the empire’s hub.

All distances in London are measured from this point in Trafalgar Square. And by extension, all distances to every corner of the British Empire were measured from here. From the sheep stations of the Australian Outback and the diamond mines of the Kimberley to the goldfields of Otago and the teeming cities of India: every place in the empire could once draw a line back to this statue of King Charles I.

But on a smaller, yet no less important level, this point in the centre of London is close to several localities that connect me to the king, the Royal Navy and the settlement of Canterbury Province on New Zealand’s South Island. The history of my family is intricately connected with this place. I, too, can draw a line from my home on the far side of the world to this statue. It is a line that bends through Africa and China, disappears back in time to the Regicide, runs through the home of the Lord Mayor of London, and into the rooms where the province of Canterbury was planned.

The statue of King Charles I is not just a tribute to a monarch. It is also a symbol of the era when Britain was expanding its global influence. In the broader context, Trafalgar Square has been a gathering place for celebrations, protests, and public discourse, reflecting the diverse and sometimes contentious legacy of the Empire.

And London itself, once the centre of a vast empire, has transformed into a multicultural metropolis that still grapples with its imperial past. The grandeur and vibrancy of Trafalgar Square are built upon layers of history that converge in this single location: a nexus of timelines, a mosaic of epochs. It is a spatial point of gravity where numerous stories, public and personal, historical and contemporary, coalesce.

On the morning of January 30th, 1649, King Charles I stepped from a window on the second floor of the Banqueting Hall onto a scaffold erected for his execution. It was a chilly morning on Whitehall, and the king, fearing that the gathered crowd would mistake his shivering for cowardice, had donned an extra shirt to keep him warm.

As he stood on the scaffold, bold, steadfast, and unflinching, the king exuded a regal dignity in the face of his imminent demise. The sombre sky above Whitehall seemed to mirror the gravity of the moment as a hushed silence fell over the gathered crowd. Before his execution, the king had reportedly delivered a speech in the Banqueting Hall, expressing his views on the reasons for the trial and his belief in his innocence regarding the charges against him. Before he laid his head on the block, he addressed the executioner, saying: “I shall say but very short prayers, and when I thrust out my hands…” This was the signal for the executioner to strike.

As he lay there on the smooth wood, the king said his final words: “I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown, where no disturbance can be.” These words reflect his strong faith and his belief in the divine right of kings, even in the face of death.

The air was thick with tension, a palpable mix of fear, awe, and the grim finality of the sentence. As the executioner raised his axe, a glint of cold steel against the grey of winter, the was a collective intake of breath. The blade descended with a swift, merciless finality, severing not just the king’s head but an era of monarchy. The sound of metal cleaving flesh and bone echoed across the street, a chilling reminder of the brutality of power, revolt and retribution. At that moment, British history was rewritten in royal blood. The reverberations of this act would echo through the centuries. They would be felt even in the distant corners of an empire that was yet to be fully realised.

The execution of Charles I was the culmination of the long and complex conflict between the monarchy and Parliament that characterised the English Civil War. The reasons behind their decision to execute the king were rooted in political, religious, and social turmoil that had been building for years.

One of the core issues was Charles I’s belief in the divine right of kings and his attempts to govern without Parliament. This led to significant tension and conflict. His autocratic rule, marked by arbitrary decisions and financial demands without parliamentary consent, deeply alienated many of his subjects and members of Parliament.

Religion also played a significant role in these tensions. Charles I’s marriage to a Catholic princess, Henrietta Maria of France, and his perceived sympathy towards Catholicism, were contentious issues in a predominantly Protestant England. His policies, seen as an attempt to impose high-church Anglicanism, alarmed Puritans and other Protestant groups who feared a return to Catholic practices.

The English Civil War, which began in 1642, was a direct result of these tensions. The war saw the country divided between Royalists (Cavaliers), who supported the king, and Parliamentarians (Roundheads), who opposed his rule. The Parliamentarians’ victory in the war, particularly after significant battles such as Naseby in 1645, led to Charles I’s capture and imprisonment.

Following his capture, attempts were made to negotiate a settlement between Charles and Parliament. However, Charles’s refusal to concede to key demands, including substantial limitations on royal authority, led many to believe that no lasting peace could be achieved while he remained alive. His perceived treachery and unwillingness to compromise were seen as a direct threat to the nation and its governance.

Ultimately, the decision to execute Charles I was as much a political statement as it was an act of retribution. It was intended to signal the end of absolute monarchy and the divine right of kings in England, establishing the precedent that the monarch was subject to the law and could be held accountable by the people, through their representatives in Parliament.

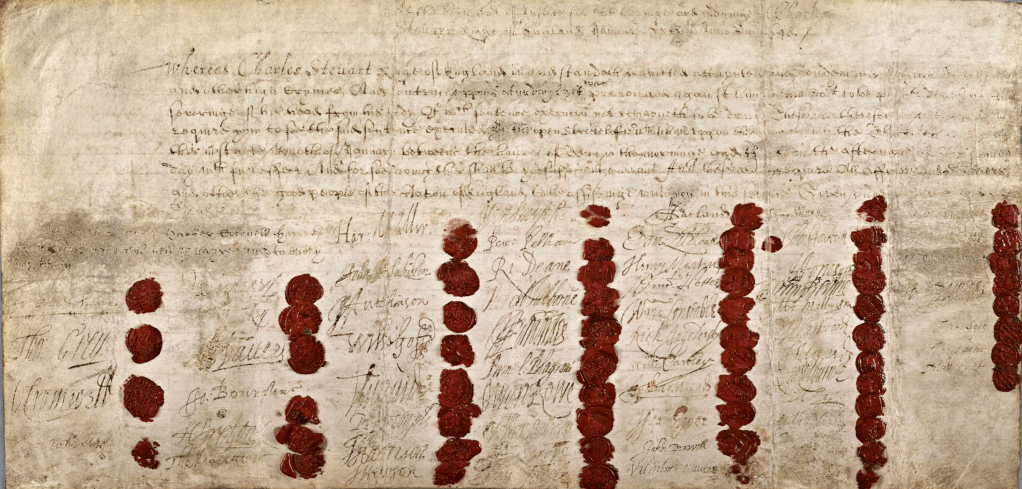

The Death Warrant of King Charles had been signed by 59 men, one of whom was my ancestor John Blakiston. Born in 1603 in Sedgefield, County Durham, John was the third son of Marmaduke Blakiston, a Prebendary (senior clergyman) of York and Durham Cathedral. In 1626, John married Susan Chamber and became known for his strong financial support of Puritan migration to America, despite never leaving England himself.

Blakiston served as a member of parliament for Newcastle in the Long Parliament, expressing republican ideas, but only took his seat in 1641 due to a contested election result. He was elected Mayor of Newcastle in 1645 and was granted an allowance during his tenure. Additionally, he was given the position of coal meter in Newcastle, a lucrative post.

As a commissioner of the High Court of Justice in January 1649, Blakiston was the 12th signatory on King Charles I’s death warrant. He passed away in June 1649. Following the restoration of the monarchy, Blakiston’s estate was confiscated by the sheriff of Durham.

The signatories of Charles I’s death warrant were members of a radical faction within Parliament who believed that executing the king was necessary to ensure the survival of the parliamentary system and prevent the return of a tyrannical monarchy. Their actions set the stage for a brief period of republican rule under Oliver Cromwell, though the monarchy would eventually be restored in 1660.

It is widely believed that some of the men who signed King Charles I’s death warrant did so with reluctance or under pressure. The atmosphere at the time was charged with political and military tension, and the decision to execute a reigning monarch was unprecedented and fraught with uncertainty about the future.

Those in power within the Parliamentarian faction, particularly the more radical elements such as the New Model Army’s leadership, were determined to bring the king to justice. This created an environment where dissenting opinions were not easily tolerated, and there was significant pressure to conform to the majority’s decision.

Some of the signatories may have also been motivated by a fear of retribution should they oppose the decision. In the volatile political climate of the time, being perceived as a Royalist sympathiser or an obstacle to the Parliamentarian cause could have dangerous consequences.

The New Model Army, which had been instrumental in defeating the Royalist forces, had a significant influence on political developments. Army leaders, including Oliver Cromwell, were key proponents of bringing the king to trial. Their influence meant that those who were hesitant or disagreed with the decision faced not just political but also military pressure.

The trial and execution of Charles I took place in a period of great uncertainty and confusion. The legal and moral justification for the trial, conducted by a specially constituted High Court of Justice, was dubious and highly controversial. This ambiguity may have contributed to the reluctance of some signatories, who found themselves in uncharted legal and ethical territory.

Personal conscience undoubtedly played a role in the hesitance of some signatories. The gravity of condemning a king to death, combined with the religious and moral implications of regicide, would have weighed heavily on many involved in the decision.

Despite these pressures and concerns, the 59 commissioners eventually signed the death warrant. The aftermath of the execution and the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 saw many of the regicides facing severe consequences, including execution, imprisonment, or exile, highlighting the fraught nature of their earlier decision.

Standing beside the statue, with the roar of modern London growing around me, I try to imagine the turmoil and fervour that turned on this pivotal moment in England’s history. I picture John Blakiston, looking down at the black ink of the 11 signatures already drying on the pale surface of the parchment, each stroke a testament to the tumult within. Was it conviction that guided his hand? Or was it the inexorable pull of duty? Perhaps it was the press of his peers in those charged, smoke-filled rooms that motivated him to sign a document that decided the fate of a king and indeed, a country.

I like to think he hesitated; that the quill trembled ever so slightly as he grappled with the magnitude of what he was about to do. In that moment of hesitation lay the entire spectrum of human emotion—fear, doubt, perhaps a flicker of hope for a new beginning, or a pang of despair for what was being lost.

But like every momentous event, my ancestor’s decision, whether borne of staunch belief or reluctant acquiescence, was just a thread in the broader tapestry of history, one that led directly to this place, this very moment, where past and present converge.

Standing in the sunlight of a London morning, I feel the lineage that connects me to that distant, tumultuous time: a lineage not just of blood but of the enduring human capacity to navigate the murky waters of moral and ethical quandaries. It’s a reminder that history is not a series of discrete events, but a continuum, shaped by the choices of individuals who, like my ancestor, stood at the crossroads of destiny, their decisions echoing down through the ages to reach me here.

The statue of King Charles was commissioned in 1630 by the Lord Treasurer of England, Sir Richard Weston, 1st Earl of Portland. He chose the king’s favourite sculptor, the French-born artist Hubert Le Sueur, to produce the statue at a cost of £600. I was intended to be installed int new gardens Weston was having laid out at Mortlake Park, Roehampton. The contract specified that:

the casting of a horse in Brasse bigger than a great Horse by a foot, and the figure of his Maj: King Charles proportionable full six foot, which the aforesaid Hubert Le Sueur is to perform with all the skill and workmanship as lieth in his power…

During the Civil War, Parliament ordered that the statue be removed and melted down. However, the goldsmith who was assigned the job hid the statue, producing items such as bronze thimbles, supposedly made from the statue, as proof that it had been destroyed. After the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the statue was unearthed and in 1675 it was erected on its present site by Charles II. The site had previously been occupied by Charing Cross, the last of the series of Elenor Crosses erected by King Edward I in memory of his queen in the 1280s. The present Charing Cross on The Strand is a Victorian copy of the original.

On the eastern side of Whitehall, not far from the banqueting hall where King Charles spent his last moments, a blue and yellow plaque is affixed to the wall of the imposing Georgian building at 22 Whitehall.

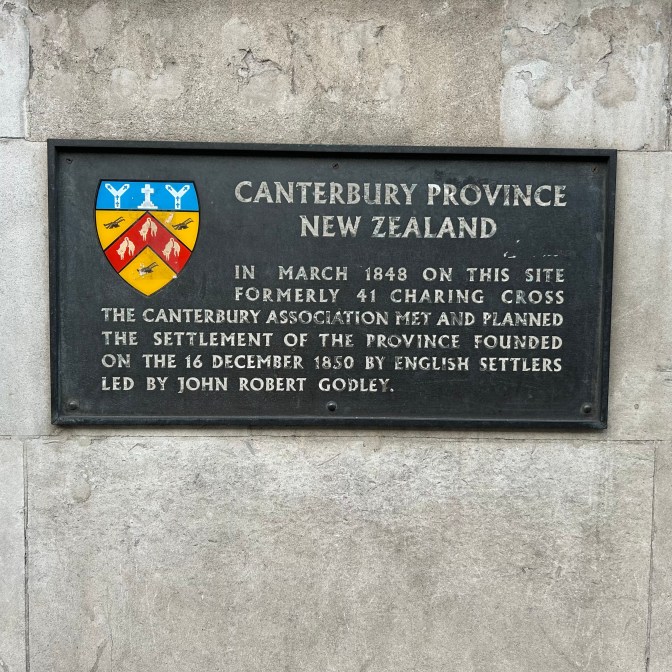

The Canterbury Association was formed in 1848, primarily under the influence of Edward Gibbon Wakefield’s theories of systematic colonisation, which advocated for the careful planning and development of new settlements. The Association’s goal was to establish a colony in New Zealand that would serve as a model Anglican society, reflecting the values, traditions, and social structures of the English upper-middle class.

Robert Godley, a key figure in the Association, played a crucial role in bringing this vision to life. Before the Association’s establishment, Wakefield had met with John Robert Godley in London to discuss the idea of an Anglican settlement in New Zealand. Their meeting laid the groundwork for what would become the Canterbury Association.

The Association’s first meeting, held near the statue of King Charles on Whitehall, marked the beginning of a significant venture that would shape the future of the Canterbury region in New Zealand. The members, who were mostly from the aristocracy and influential Anglican circles, pooled their resources and authority to carry out their vision.

The Canterbury Association’s plan was comprehensive. It encompassed the selection of settlers, the design of the settlement, and even the social and religious structures that would govern the new colony. They envisioned Canterbury as a “new England,” complete with its own cathedral, schools, and a structured society that mirrored the class divisions and cultural norms of Victorian England.

In 1850, the Association’s efforts culminated in the First Four Ships setting sail for New Zealand, carrying the first group of settlers to the Canterbury Plains. The establishment of Christchurch as the central city was a testament to the Association’s planning and vision. The city was laid out with a central cathedral square, echoing the Anglican influence that was at the heart of the Association’s mission.

The Canterbury Association was dissolved in 1852, having successfully established the settlement. However, its legacy lived on in the structured layout of Christchurch, the Anglican institutions that were established, and the societal norms that shaped the early years of the Canterbury settlement.

The story of the Canterbury Association is a fascinating chapter in the broader narrative of British colonisation, reflecting the era’s ambitions, values, and visions of utopia. It illustrates how ideas conceived in the meeting rooms of London could reach across the globe, shaping the development of new societies in distant lands.

The founding of Canterbury marked the beginning of a new chapter for many individuals from the lower echelons of English society. The settlers who arrived in this new land found themselves in a vastly different social and economic environment. It presented them with unique opportunities for social mobility and personal autonomy: opportunities that were often unattainable in the rigid class structure of Victorian England.

In England, peasants, farm labourers, and maids were often bound to their roles with little hope of advancement, their lives dictated by the whims and needs of the landowning and aristocratic classes. This hierarchical social system left little room for individual progression outside of one’s birth status. However, the settlement of Canterbury, with its vast tracts of land and the need for skilled and unskilled labour to develop it, created a different reality.

Upon arrival, many of these individuals discovered that their skills, work ethic, and determination could earn them a piece of land or a position that was previously unthinkable. The scarcity of labour and the abundance of resources meant that hard work could significantly alter one’s social and economic standing. The traditional markers of social status held less sway in this new setting, where survival and prosperity depended more on one’s ability to adapt and work hard than on one’s lineage.

This newfound freedom and the possibility of owning land acted as powerful incentives. It encouraged not only hard work but also a sense of independence and self-reliance. The egalitarian ethos that began to emerge in Canterbury and other parts of New Zealand was in stark contrast to the stratified social order they had left behind. It was a place where a former farm labourer could become a successful farmer in his own right, or a maid could become a respected member of the community through her endeavours.

The transformation of these settlers’ lives illustrates how migrating to a new land provided not just a physical but also a social space for reinventing oneself, free from the constraints and limitations of the old world.

Following the establishment of the Canterbury settlement by the Association, Samuel Butler, then a young man seeking adventure and opportunity away from the constraints of English society, arrived in New Zealand in the early 1860s. Settling first in the fledgling province of Canterbury, Butler became part of the pastoral and agricultural development that the Association’s efforts had set in motion. His experiences in this new and challenging environment, starkly different from the structured and idealised society envisioned by the Association, provided fertile ground for his later literary works.

Butler’s seminal novel “Erewhon,” published a decade after he arrived in New Zealand, can be seen as a direct critique of the very ideals and societal models that the Canterbury Association sought to implant in the southern hemisphere. The novel, with its title famously an anagram of “nowhere” — suggesting a place that is at once both familiar and utterly fantastical — presents a society where many of the norms and technologies of Victorian society are inverted.

Butler’s evocative description of Erewhon was based entirely on his memories of the Rangitata Valley where he had established a sheep station he called Mesopotamia.

I am there now, as I write; I fancy that I can see the downs, the huts, the plain, and the river-bed – that torrent pathway of desolation, with its distant roar of waters.

As I stand beside the statue of King Charles on this fine August morning, I can imagine that vast landscape. It is so different to the cityscape I see around me. Yet it is connected directly to this very spot by the leylines of history. The measuring of distances from this place in London also serves as a metaphor for the reach of the Empire and the personal journey of my ancestors. It highlights how people from the hub of the Empire ventured to its farthest corners, carrying their hopes, dreams, and the culture of their homeland. Each narrative is a thread that spans the globe and returns, gathering stories and measuring the distance to here.