I’m at the end of a new frontier

Here at the edge of the flat earth ending

I’m getting off to get lost in the air

At the end of the world where the light is bending.

– Counting Crows, New Frontier

Sunday morning in St David’s. Crows wheeling above the town. Their strident calls resound across the rooftops of the city and out across the valley of the River Alun. A grey sky with scratches of blue promises a fine day to come. The cobbled street is silent and empty as I descend towards an ancient stone gatehouse. It is as if the modern world has receded into an echo or a memory, like a ghost image on my retina.

The gatehouse has the weathered patina of centuries. As I walk beneath it I hear the footfalls of pilgrims and patrons: a soft chorus of the sacred and the profane. Skeptics and believers, sinners and saints, paupers and kings have all passed beneath this gateway, with its twin arched aisles and its double portcullis. Here in this far south-western corner of Wales I am on the outer edge of the world. Not far from where I walk, the cliffs and coves of Pembrokeshire give way to St. George’s Channel, the Celtic Sea and the ominous, swirling billows of the Atlantic.

I cross the threshold of the gatehouse and step into the expansive, open grounds of the the cathedral. Before me, a grassy bank leads down to the valley floor where the cathedral sits, perfectly framed by copses of elder. A tracery of dry stone walls — etched white and grey with lichen — edge the cemetery with its spartan collection of canted and broken headstones. Beyond it, the ruins of the Bishop’s Palace, nestle against the valley’s opposite side.

The cathedral itself stands venerable and solemn. Its old stones, worn and weathered by time, seem poised to tell stories of ages past, like a monk awaiting a calm moment to impart wisdom. Standing here, at what seems like the very brink of the British Isles, I can feel the boundaries between history and legend blur. The cathedral, magnificent, grave, regal and austere, anchors the town in its medieval past. It is not merely a structure but a sentinel watching over the coming and going of generations.

This is a place where the spiritual and the earthly, the transcendent and the temporal, seem to converge. And on this August morning, the cathedral seems to gather the susurrations of the past and the voices of present into its still-shadowed walls. In my subconscious I can hear it mutely whispering: “come and find out.”

Sometimes, when travelling, I find a place that I have never head of that turns out to be so captivating and amazing that it becomes part of my long list of favourites. And the Eglwys Gadeiriol Tyddewi (St. David’s Cathedral) is one of those places.

St David’s is the United Kingdom’s smallest city. With a population of only 1,750 (five hundred people less than my hometown, Geraldine, on the South Island of new Zealand) it seems more like a village than a city. However, according to ancient British lore, if a place has a cathedral, it qualifies as a city. St. David’s and its cathedral owe their origins to St David, the patron saint of Wales, who established a monastic community here in the 6th century. The site was chosen for its remote and serene location, offering a perfect setting for devout meditation and religious solitude.

The construction of the cathedral that stands today began in the 12th century under the guidance of Bishop Peter de Leia. It has endured through myriad challenges over the centuries, including Viking invasions and the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII. Despite these tribulations, the cathedral has been continually expanded and beautified, reflecting the architectural styles and ecclesiastical tastes of each successive period.

St David’s was granted city status in the 12th century and it has remained a place of pilgrimage and religious significance right down to the present day. Its popularity among pilgrims, prior to the establishment of the cathedral itself, was greatly increased by a decree from Pope Calixtus II (1065-1124) that making two pilgrimages to St David’s were the equivalent of making one to Rome. The money that pilgrims brought to the area allowed construction of the cathedral to begin in earnest. And as well as the common folk seeking enlightenment and a direct route to heaven, medieval luminaries who made pilgrimages to St. David’s included William the Conqueror in 1077, Henry II in 1171, and Edward I and his queen, Eleanor, in 1284.

I descend a series of wide flagstone steps to the cathedral grounds. Up close, the building is comfortingly stolid. Its flat-topped, unadorned tower stands four square above the crossing, where the north and south transepts intersect with the nave. The stone walls are warm to the touch, etched with lichen and moss, and stained by the centuries of rain that have fallen upon them.

The tower, which once contained the cathedral’s ten bells is now empty. The bells were removed in 1730 when severe structural faults were discovered in the tower. The massive weight of the bells, bearing down on the footings and walls, were thought to be in imminent danger of collapsing the entire structure. The bells lay in obscure, silent storage for two centuries until the 1930s when an anonymous donor paid for them to be resurrected in the Porth y Twr: the gatehouse that I have just walked through.

As I walk along the south wall of the nave, running my hand across the textured stone, a single bell begins to toll. The cathedral’s tower serves as an auditory transmitter, sending the sound out into the surrounding countryside. At the sound of the bell, the circling crows begin an echoing chorus: a discordant counterpoint to the sonorous peals. It is a wonderful sound, redolent with history and a resonance that, to me, defines the ecclesiastical landscape of Britain.

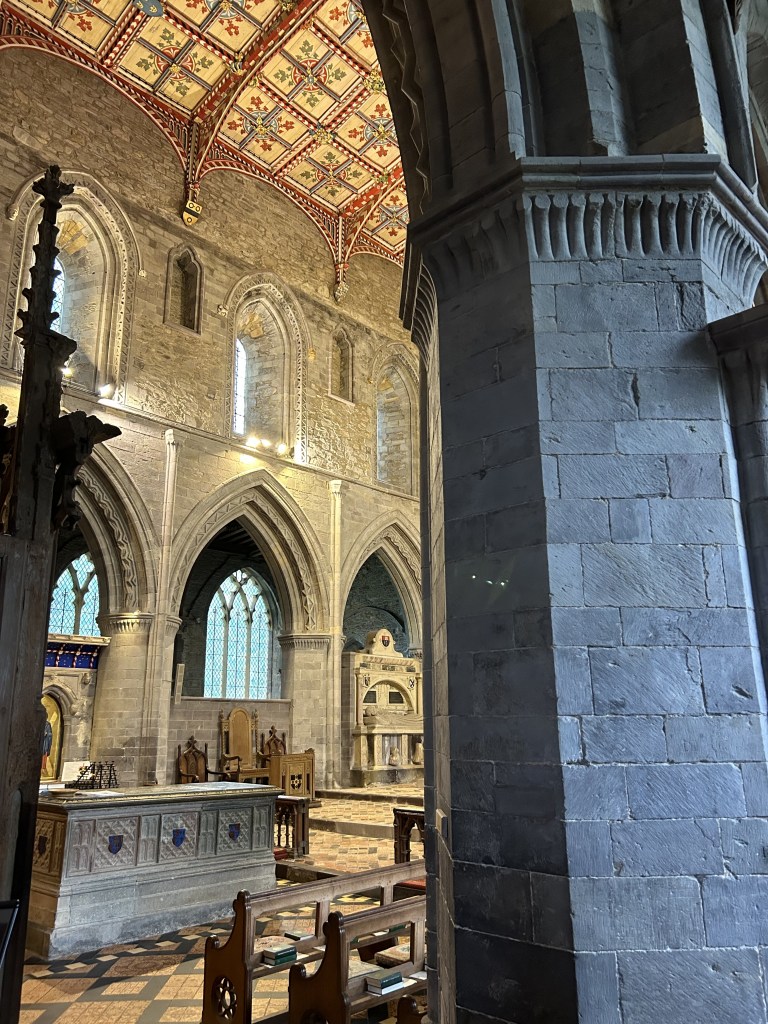

I enter the cathedral via the west narthex. The heavy door, hung by massive hinges of wrought iron, creaks slightly as I open it. I feel a slight exhalation of warm air from within, as if the cathedral is breathing. I step into the vestibule and the silence. Immediately, my eyes are drawn upwards by the great stone pillars to the ornate timber ceiling. Decorated with geometric inlays, the square wooden panels of Welsh oak are picked out in shades of blue, red and buttery yellow. Completed in the 1530’s, the ceiling is unique in Britain: a masterpiece of its age. Huge pendants of carved wood, like the knees and spirketting of an inverted, age-of-sail ship’s hull, hang from the ceiling: architecturally and spiritually unnecessary but adding an impression of sturdiness, longevity, grandeur and immutability.

At this hour — 7 AM — the cathedral is still closed to the public. But morning prayers are underway so I take a pew halfway up the nave and sit listening to the cadence of incantations and murmurs emanating from an unseen chapel deep in the sanctuary. There is something undeniably evocative and captivating about listening to prayers in an ancient church. As a completely irreligious person, I have no belief in gods, holy spirits or the afterlife. Nevertheless, hearing these solemn invocations in a setting such as the cathedral at St. Davids is still incredibly moving and profound.

I walk slowly up the nave towards the quire screen, an ornately-carved stone barricade separating the main body of the cathedral from the high altar and the twin chapels beyond.

In ecclesiastical architecture, the primary function of the quire screen — which are also known as Rood Screens — is to separate the chancel, which houses the high altar, the choir, and the rear chapels, from the nave where the congregation gather. This separation underscores the distinction between the clergy and the laity, both spatially and symbolically. Quire screens also support some of the practical aspects of liturgical ceremonies. They often feature a loft that can be used for readings, performances of sacred music, or as a place for the rood—a large crucifix which would often be accompanied in procession through the cathedral by statues of saints and other biblical figures.

Quire screens are also elaborately decorated with sculptures, paintings, and carvings that depict various religious stories and themes. These artworks serve both an educational purpose — teaching the illiterate masses of old the biblical stories and themes of Christianity — and an aesthetic one, beautifying the sacred space. The screens also had a symbolic role as a veil between the earthly realm of the congregation and the sacred realm of the clergy and the sacraments. This reinforced the mystery and sanctity of the religious rites performed beyond them.

The structure of the quire screens also helps to project the voices of the clergy and choir towards the congregation, enhancing the auditory experience of the services. In the days before wireless mikes and digital surround sound systems, this was an important part of maintaining the atmosphere of glory and spectacle that churches relied on to keep their congregations interested and the cash flowing into the offertory.

Beyond the quire, the High Altar draws me towards the spiritual heart of the cathedral. The tombs of Lord Rhys ap Gruffydd, Edmund Tudor and St. David himself flank the altar. An ensemble of pointed arches and Gothic ribbed vaults soar heavenward: an effect that the architects envisaged would draw the eyes upwards in reverence and awe. The altar itself stands beneath three opulent reredos. These decorative screens, crafted to resemble windows, are inset deeply into the rear wall of the High Altar space. They give the impression of looking through portals, each one framing a sacred narrative, as if the viewer is gazing into a spiritual dimension beyond the physical dimensions of the cathedral. The window-like design of the reredos enhances the depth and perspective of this sanctified space. They also symbolically open up the wall, inviting the viewer to contemplate the divine stories of Christian lore that they depict.

Above the reredos, three clerestory windows of intricate stained glass permit a cascade of light to enter, bathing the altar in a soft, diffuse glow. It is a serene yet powerful space, at once transcendent and ethereal. Yet even though I am almost transfixed by the scene, I am also conscious that, as an unbeliever, I am an imposter, a mere spectator in this holy place. I hear footsteps and low voices approaching. The cathedral is awakening; beginning another spiritual day in the temporal realm it has occupied here on the edge of the world for eight hundred years. It is time for this heretic to leave this sacred sanctuary.

As I step from the High Altar into the North Transcept, I pause to place my hand upon the shrine of St. David. I feel sure that, whatever my beliefs, the Patron Saint of Wales would not begrudge me my visit to this lovely, sacred place.

I walk back up the nave and stand beneath one of the twin rose windows in the west end wall of the cathedral. Beneath it, a small electronic kiosk allows modern pilgrims to make a donation towards the upkeep of the cathedral. As I swipe my watch against the screen to contribute £10, I think of the countless other wayfarers who have gone before me. Kings and queens, warriors and wastrels, the blind, the halt and the lame, peasants seeking penance, poets seeking inspiration, and travellers on ancient roads have all stood in this same place.

As the virtual offertory accepts my digital oblation, I hear the echoes of their footfalls and their lustrations down the ages. For I, too, am a pilgrim on this ancient road. And while I do not seek spiritual enlightenment, I draw solace in the fact that I have serendipitously discovered a place that I revere as profoundly as any believer. I step outside, moving from this old frontier of prayers and whispers to the new frontier of bending light and wheeling crows. And the bells begin to toll.