They determined on walking round Beechen Cliff, that noble hill whose beautiful verdure and hanging coppice render it so striking an object from almost every opening in Bath.

– Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey

Mid-morning in Bath. Through the open window beyond my coffee cup I watch the River Avon slip gently over the weir below. Swallows flit and dive through the shimmering, pellucid air. Circling pigeons come to rest periodically on the limestone crenellations of Pulteney Bridge. On the right bank of the river, the ornate facades along Grand Parade rise in a stately, solid pile.

It has been a busy morning. Awake at 5 AM I had walked across the fields behind Dymock, where late summer mists hung in the valley bottoms and the azure sky, striped with sunrise cirrus, had promised a fine day to come. We’d left the house a 6:30 and driven to Bristol where Lydia and Emma had caught a flight to Europe.

With no firm plan, other to be in Lydiard Millicent at 2 PM, we’d decided to visit Bath. It was on the way, after all. And for more than than two thousand years people have been stopping by to visit the hot pools, to “take the waters”, and to commune with the various gods that have always been worshipped in this deep Somerset valley.

Bath sits upon a stratum of Jurassic limestone interspersed with layers of clay underlain with impermeable basement rocks. Faults in this rock allow water to seep into the Earth’s crust where it is superheated by geothermal energy. As the water heats up it expands and becomes pressurised, rising back to the surface to form the hot water springs at Bath. These springs, the only ones in the United Kingdom, emerge from the ground at a constant 46°C. Enriched with dissolved minerals absorbed from the rocks through which they ascend, the three main springs — the King’s Spring, the Hetling Spring and the Cross Spring — have been the centre of human life in the area for millennia. Their high mineral content, particularly the sulphates, chlorides and bicarbonates of calcium and sodium, have always been believed to have healing properties.

Long, long before the arrival of the Romans in circa CE 43, the springs were used and revered by Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age peoples. The Iron Age saw the construction of hill forts around Bath, such as the one at Little Solsbury Hill, the place that inspired Peter Gabriel’s song Solsbury Hill. When Celtic tribes occupied the area, they dedicated the springs to their goddess Sulis.

When the Romans turned up in the first century of the Common Era, they established a structured settlement they named Aquae Sulis, transfiguring the Celtic goddess into a deity of their own. They constructed sophisticated bathhouses and a temple dedicated to Sulis Minerva, merging the local traditions with the bathing culture that was an essential part of Roman life. Their structures were engineered to an extremely high standard, with hypocaust (underfloor) heating and intricate networks of lead plumbing.

Bath flourished as a centre of both commerce and religion throughout the Roman occupation of Britain. Archaeological excavations have unearthed numerous artefacts from this period including one particularly strange set of relics: curse tablets. More than a hundred of these small lead or pewter scrolls have been found. They are inscribed with prayers and exhortations to the goddess Sulis Minerva asking for action against specific wrongs or injustices that the individuals evidently thought had been visited on them. Whether or not these Roman versions of fighting a speed camera ticket were successful or not, history doesn’t record.

By the seventeenth century, Bath had evolved into a fashionable spa town. The benefits of “taking the waters” at Bath, were promoted by luminaries in the field of medicine such as Dr. Thomas Guidott. His book A Discourse of Bathe, and the Hot Waters There, published in 1676, drew a clientele of wealthy and influential patrons to the town. During the eighteenth century, the city’s most iconic architectural features were laid out, including the Circus and the vast semi-circular residential development called the Royal Crescent. This period of grace and gentility cemented Bath’s reputation as one of Europe’s premier resort destinations. And along with the nobility and gentry, notable literary and artistic figures such as Mary Shelley (who wrote Frankenstein while living in Bath), Jane Austen, Anna Sewell and Charles Dickens became frequent visitors.

For my part, as well as associating Bath with the music of Peter Gabriel — his Real World Studios, where bands such as Tears For Fears, Marillion, Elbow, Muse and The Waterboys have recorded is located on the outskirts of Bath— the Aubrey-Maturin series of nautical novels by Patrick O’Brian often reference the city, particularly Laura Place and The Pumphouse.

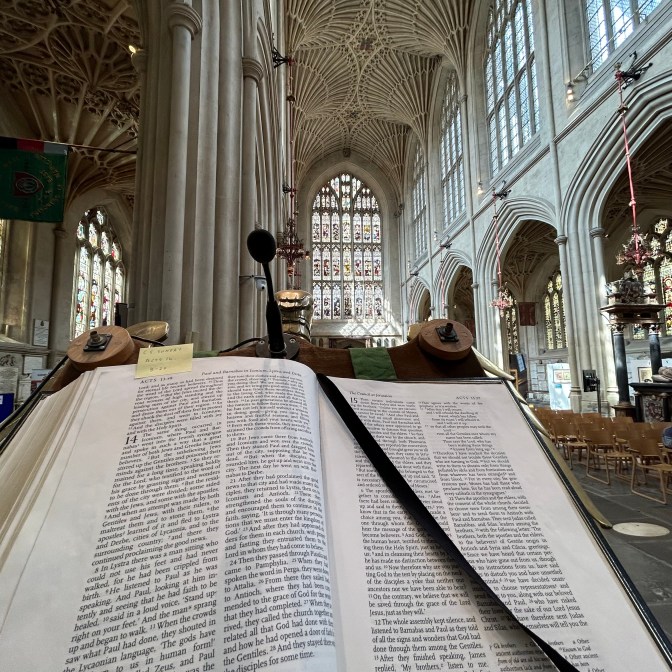

Bath Abbey already has a crowd of visitors waiting in line outside the south door. As we join the queue of latter-day pilgrims I look up at the Abbey’s worn Gothic facade. It is etched and melted by acid rain and the passage of centuries. Gargoyles and chimaeras stare sightlessly from the cornices, their visages dissolved into grotesque rictus grins and macabre grimaces. Stepping into the vestibule is no less unsettling. I feel as though I am entering a portal that will transport me back into the Dark Ages, when superstitions ruled the minds of men and flickering torches cast ominous shadows on cold stone walls.

But then, as we move into the Abbey’s expansive nave, the focus and mood shifts. The air is suddenly filled with light. It streams through the encircling panorama of stained glass windows, bathing the honey-coloured Bath stone in its almost rapturous glow. I can immediately feel the spiritual power that this place exerted on its congregations. Washes of colour cascade through the hazy, luminous immensity of the nave, painting the statuary and arches with vivid shades and casting discreet shadows into the alcoves and corners.

Linda wanders off to explore while I simply sit on a pew beneath a gryphon erupting from the front of the ornate wooden pulpit. Once again — as I will be many times on my travels in England and Wales — I am captivated by the transcendent splendour of this place of worship. Free of any religious beliefs I am able to appreciate the interior of the church for its profound ecumenical artistry and grandeur. It is in these moments, surrounded by these great monuments to belief, reverence and dedication, that I experience my own introspective revelations: not so much spiritual as reflective and enlightening.

Linda finds me and presents me with a hand-made, leather-bound journal with my initials, FAJB, stamped on the cover. It is a perfect gift for recording my thoughts here in Bath Abbey. I write: “The limestone columns soar into a firmament of flutes and filigree. And where Westminster Abbey seemed cramped and cluttered, the luminous immensity of Bath Abbey seems full of light and space.”

From the Abbey, we repair to the The Colombian Company on the far side of Kingston Parade for a coffee. The great flagstone expanse of the Parade is awash with people: street performers, shuffling groups of package tourists following flags held aloft by their guides, flunkies, junkies, derelicts and dossers, pigeons and panhandlers. It is a tableau that has been repeated here daily for centuries. These old stones, watched over by the petrified saints and brooding gargoyles of the Abbey, have seen endless gatherings swirling in and out of the time passages that run to and from this square. It is only the colours and the shapes — and the addition of digital devices — that have changed.

After our coffee, we walk uphill to the Royal Crescent. On the way up Gay Street we pass the house where Jane Austen penned some of her most famous stories. I picture her, working by the light of a candle, describing Mr D’arcy and life in Georgian England, or seated at her modest wooden desk with the soft murmur of Bath’s social gatherings drifting in through the open window. It was these sounds, along with the clatter of horse-drawn carriage wheels on cobbled streets, and the whisper of distant conversations, that inspired and fueled her keen and witty observations of early nineteenth century mores and manners.

At the end of Brock Street, the Royal Crescent sweeps around in splendid arc of pale Bath limestone, Doric columns, black-painted wrought iron and neatly-trimmed ornamental trees. Designed by the architect John Wood the Younger, the neo-Classical stylings of the Royal Crescent embody the opulence of the mid to late eighteenth century. The precision of its architectural symmetry, where every cornice and scroll plays a considered role in creating a cohesive whole, is also the outward expression of the orderly and controlled world that lay behind each door.

This perfect symmetry was reflected by life within the houses of the Royal Crescent. The precise dimensions of the mantlepieces, the arrangements of leather-bound books on the shelves, the mirror-image perfection of the furniture, even the melodies of Mozart and Handel, all contributed to the stability and longevity of the world that the Georgians had created for themselves.

In his book Civilisation (1969), the art historian Sir Kenneth Clark describes Georgian life as: “a finite, reasonable world; symmetrical, consistent and closed.” With a rigid hierarchy and meticulously prescribed social codes, each household functioned with the well-oiled accuracy of a Breguet timepiece, mirroring the architectural harmony and order visible outside their elegant windows.

Of course, when a world becomes closed it also becomes oppressive. So it was no wonder that poets such as Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron and Keats longed to break free of the strictures imposed by this stifling, regimented world and escape into the freedom of what they called The Sublime. Even the heroines created by Jane Austen, whose novels exemplify the rigorous behavioural codes of Georgian England, strove to transcend this inflexible world.

We perambulate around the Royal Crescent then cross the neat, grassy lawn below and descend Royal Avenue to Queen Square. Linda goes off to have her nails done; I walk back to the Pulteney Bridge. The same table where I sat earlier is still vacant. I really don’t need another coffee. But the thought of sitting there again, writing up my notes while I look out over the river is too enticing. I order a latte and take my seat again, a modern pilgrim in an ancient city, writing his chronicles at a table in a room with a view.