I’m a traveller just passing through…

– Sharon O’Neil, Asian Paradise

In China, parks and natural landscapes hold a revered place in the cultural fabric of society.

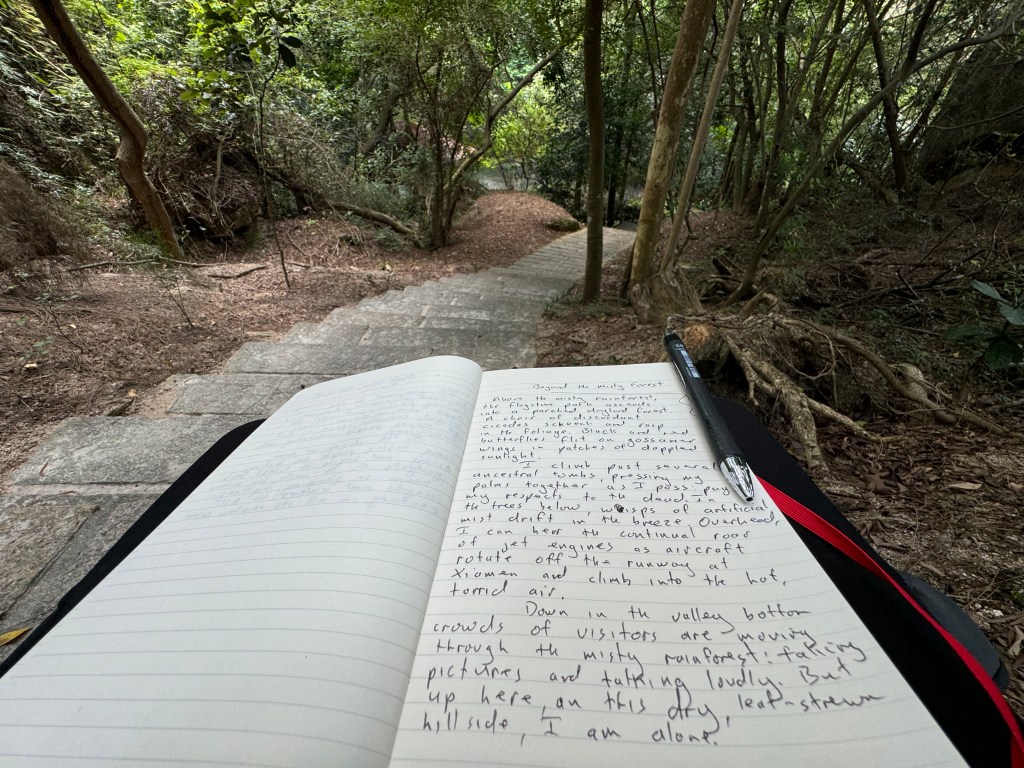

Above the misty rainforest, the flagstone path ascends into a parched dryland forest. A choir of discordant cicadas screech and rasp in the foliage. Black and red butterflies flit on gossamer wings in patches of dappled sunlight.

I climb past several ancestral tombs, pressing my palms together as I pass, paying my respects to the dead. In the trees below, wisps of artificial mist drift in the breeze. Overhead, I can hear the continual roar of jet engines as aircraft rotate off the runway at Xiamen Airport and climb into the hot, torrid air.

Down in the valley bottom, crowds of visitors are moving through the misty rainforest, taking pictures and talking loudly. But up here on this dry, pine-clad hillside, I am alone.

The cicadas fall silent momentarily in response to some subtle change in temperature or humidity. The mist in the hollow reverses direction, swirling up to envelop the path below. Ants explore the weathered stone of the step I sit on. I can hear laughter and voices echoing up from the misty rainforest.

The air is heavy with the astringent smell of pine; the ground latticed with fallen pine needles, brown and desiccated. Below me, in the hollow, a family takes photographs with their phones in a tiny wooden shrine. The September heat crackles in the trees. I have recovered my breath from the climb and cooled down after the humid, enervating heat of the rainforest below. The stridulation of the cicadas begins again, louder than before as if they are challenging the silence that has settled over the landscape. I swallow a few mouthfuls of precious water from my bottle, and continue upwards.

The Chinese love of parks

In China, parks and natural landscapes hold a revered place in the cultural fabric of society. Rooted deeply in traditions that celebrate the harmony between humanity and nature, Chinese parks are not just spaces for leisure and relaxation, but also spiritual and meditative retreats where the natural world is meticulously sculpted to reflect philosophical ideals.

These green spaces serve as the communal hearts, lungs and souls of Chinese cities. Their layout, aspect and design embody a collective appreciation for nature’s tranquility and its restorative powers. Ancient trees stand alongside carefully sculpted waterways spanned by arched and zig-zag stone bridges, shaped to fend off evil spirits who are said to only move along straight lines. Music emanates from speakers discreetly hidden in the verdant foliage. Elegant pavilions, embodying the classical principles of Feng Shui that aim to balance and enhance energy, provide shade and shelter in discreet hollows and inglenooks.

Primordial phantoms of romance

Not content with adjusting the landscape itself, Chinese garden designers often add special effects to augment and enhance the atmosphere of Chinese parks and green spaces. In the case of the Misty Rainforest, deep in the centre of the Xiamen Botanical Gardens, fog machines blow tendrils of fine mist into the spaces between and around the vegetation.

These ephemeral streamers envelop and shroud the vegetation as if it is the setting of a fairy tale. The mist curls through the trees like primordial phantoms of romance, cascading over the tinkling waterfalls and floating like gossamer pollen in the still air.

Pixel calligraphy

In Chinese parks, the bustle of urban life fades to a distant echo. People of all ages practice tai chi, play traditional music, partake in birdwatching, stroll arm-in-arm with friends or sit quietly by themselves. And, of course, they indulge in the Chinese obsession of taking endless selfies and portraits on their devices.

In the Misty Rainforest, I had been in the midst of this digital frenzy. I moved through a throng of visitors capturing their presence in the mist-shrouded vegetation and blossoming flowers with their smartphones, transforming every spot into a backdrop for personal expression.

This modern passion for digital photography echoes the historical Chinese reverence for the arts, where the capturing of nature’s essence was once pursued through brush and ink rather than pixels. In ancient China, literati painters and poets sought to embody the spirit of the landscape through calligraphy and watercolour, seeing their artistic endeavours as a form of personal and spiritual fulfilment.

Today, this tradition lives on in the form of digital photography, where each snapshot serves as a digital brushstroke, intertwining the past and the present. The ubiquitous smartphone cameras in the hands of every park-goer are not merely tools for capturing moments: they are the latest instruments in a long lineage of Chinese artistic expression, seamlessly merging traditional artistry with contemporary technology.

Butterfly Lovers

In a small glade I’d watched a young couple having their wedding photographs taken. The bride was dressed in a long, flowing dress of white and pastel pink. She held a bouquet of pink and white roses and wore a floral crown of orchids. The groom was impeccable in a white tuxedo with a single pink rose on his lapel.

The swirling mist and dappled light gave the scene a mystical, ethereal quality, reminiscent of the legend of the Butterfly Lovers. This is one of China’s most famous love stories, often considered the Eastern equivalent of Romeo and Juliet. The tale describes two lovers, Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai, whose forbidden love leads them to transform into butterflies in order to escape from the societal constraints of their time.

In the story, a romance develops between Zhu Yingtai, a young woman, and Liang Shanbo, her classmate. As schooling is forbidden for women, Zhu has had to disguise herself as a man to attend school. In class, she meets and forms a deep bond with Liang. Over time, Zhu falls in love with Liang but struggles to reveal her true identity. When Zhu is forced into an arranged marriage with another man, she invites Liang to her home, hoping he will claim her as his own.

However, Liang fails to realize Zhu’s feelings and her true gender until it’s too late. Heartbroken upon discovering the truth, Liang dies of despair. On the day of Zhu’s forced marriage, she visits Liang’s grave, which opens up and envelops her, allowing their spirits to emerge as butterflies, flying away together, finally united in death.

Just like Romeo and Juliet, the tale symbolises eternal love and the struggle against traditional societal norms. In this respect the story mirrors Chinese society today. The young people of modern China are also seeking to carve out identities that resonate more authentically with their personal beliefs and aspirations. However, the layers of traditional societal norms make this quest for self-expression and individuality a difficult task.

Nevertheless, as I ease myself into Chinese life, I have begun to gain a better understanding of the social undercurrents at play: currents that ebb and swirl like the tendrils of fog in the Misty Rainforest. These currents signal a palpable shift among the youth of China, a move towards self-expression and more diverse lifestyles powered by digital connectivity and global influences. This shift is reshaping their identities and broadening their perspectives, signalling a significant transformation in the cultural fabric of modern China.

High and Dryland

The path continues upwards through the conifers and casuarinas to a plantation of cacti and desert vegetation. Up here, the sun beats down with almost tactile force; the glare from the parched, white ground is incandescent. Oversized plastic representations of cartoon characters peer from spiny and spiky clumps of succulents. Families wave selfie sticks around as they crouch in the shadows to capture memories.

The New Stele Forest

I climb another concrete stairway into a dense forest of casuarina trees growing among giant granite boulders. In places, the path is cut directly into the rock; in others, it wanders around shaded bluffs on steel catwalks. I catch glimpses of the city through openings in the canopy. Occasional breaths of cooling wind refresh me, momentarily at least.

The cold, electronic eyes of surveillance cameras, bolted to steel poles at each intersection, watch me as I climb. A malfunctioning speaker emits an alien crackle of incomprehensible static that sounds like the Scavs in the movie Oblivion. This deep state paraphernalia doesn’t faze me, however. Indeed, the constant gaze of cameras is somehow comforting in the confusing world of modern China I have chosen to immerse myself in.

I imagine myself passing out from dehydration or exhaustion in this lonely place. Soon after, a team of rescue paramedics, alerted by some distant algorithm, abseil from helicopters to save me. In China, even the most remote locations come with high-tech guardian angels.

I stop to rest at set of wrought iron tables and chairs that wouldn’t look out of place in a Plantagenet garden in England. They have been placed, somewhat incongruously, on this Chinese hillside between a pair of tall granite boulders overhung with casuarina trees and bamboo. A lovely cool breeze funnels through the gap and I have a hazy view of Xiamen framed by branches and boughs.

I drink the last of my water — I have, foolishly, walked past several vending machines without topping up — and sit quietly, letting the effects of the Ideal Gas Law cool me down. Nothing says refreshment like a good dose of PV=nRT in action and as evaporation cools my skin, I scroll my WeChat feed and scribble a few hasty notes in my diary. I am completely alone in this strange, exotic place. I reflect that, despite the digital web of social media threads that extend outwards from my phone to the world, nobody knows where I am. Here, in the vastness of China, I am simultaneously tethered to the familiar and adrift in the unknown: a digital castaway, connected yet disconnected, obscured by the foliage of the world’s most populous nation.

The Boulder of a Thousand Scepters

A steel stairway leads from the clearing up to the top of hill. From the viewing platform I have a panoramic view of the gardens with the towers of Xiamen beyond. Far below, a crew of workers are clearing a section of trees and scrub. The sound of their voices, interspersed with the occasional clattering roar of a chainsaws, echo up from the shimmering gully where they are toiling. Below them, and further to the right, the orange tiled roofs of the Lotus Temple stand amid a shroud of tropical vegetation.

I leave the clear air of the summit and clamber back down through the forest along precipitous pathways and circuitous stairways cut into the clay. A heavy carpet of pine needles covers the forest floor, softening and rounding the rough ground. Shuffling beams of sunlight make their way down through the canopy.

Beside a boulder with several steps carved into it, the path forks. Unsure of which way to go, I clamber up the steps and emerge, blinking, onto a vast platform of weathered granite. From this vantage point, suspended halfway between luxuriant greens of the park below and the hazy dome of the sky — a sky too hot to be blue — I plot my descent into the valley. I am closer to the Lotus Temple now, its bare courtyards and tiered terracotta roofs ranged around a gigantic boulder and shaded by spreading cypress and juniper trees.

I set up my monopod and take a few selfies (as you do in Chinese parks: see above) standing on the edge of the void. It is in places like this are where I am at my most reflective when I am travelling. Standing alone on some eminence or outcrop, with a mysterious, verdant, as yet unexplored landscape, pastoral expanse or urban labyrinth spread out before me, I always feel a deep connection to my journey. It’s an immensely pleasant sense of being at once insignificant, untethered and invisible, yet inextricably drawn to the infinite possibilities that take me back to the road time after time.

Presumably, I think, there is some esoteric Buddhist lesson hidden deep within reflections such as these. Perhaps the answer lies within the walls of the Lotus Temple. I leave the rock to the sun and the sky and descend through the forest towards the temple: a kind of inverse ascent to Nirvana where I will find wisdom, clarity and enlightenment.

Alone in the Lotus Temple

I approach the temple doors with a mixture of apprehension, reverence and curiosity. Even though I know that places of worship and contemplation — Christian churches, the mosques of Islam, the temples of Confucius and the Buddha — are always welcoming, I still feel like something of an intruder: a voyeur, peering into sacred spaces that hold meanings beyond my understanding.

The twin red gates of the temple stand ajar, guarded by a small, effigy of the Buddha, sitting cross-legged with his hands clasped in prayer. His expression is at once cheerful, pacific and beguiling. I climb a set of flagstone steps to the courtyard. It is empty. The prayer halls are silent; the faint scent of incense lingers in the still air. The shadows of the overhanging trees ripple across the flagstones, moving almost imperceptibly as air currents tremble their leaves.

Stone and sky

Still feeling like an imposter, I tread slowly through the temple complex, as though the quiet might shatter at the sound of my steps. There are no prayers, no lustrations, no chants. The recondite wisdom inscribed on the boulders is incomprehensible to me. Alone in this sacred place, I am enveloped by a profound stillness, a stillness that seems to extend beyond the physical. It is as if the temple walls, the rearing boulders, the graceful trees and the sheltering sky are all breathing in silent unison, holding centuries of spiritual contemplation within their temporal embrace.

Samsara and me

Although I still have a long walk ahead of me — down to the luxuriant forest around Wanshi Lake, across the colourful gardens of the Araucaria Lawn, not to mention the descent back into the urban chaos of Xiamen — I linger in the temple. Sitting in the shade of an ancient cypress, with the beneficent gaze of three golden Buddhas watching over me from the prayer hall, and the boulder of A Thousand Sceptres Facing Skywards (一千根权杖指向天空) rearing above me, I am acutely aware of my own transience: both in this place and in the silken thread of time. This moment is just a single asterism — a convergence of history, nature and thought — in the endless cycle of life, decay and rebirth that Buddhists call samsara.

The hiss of cicadas rises and falls with the rhythm of the surrounding forest, while the scent of pine needles and incense lingers in the air. In the distance, the hum of the modern city calls me back to the world of noise and movement, but for now, I remain suspended in this moment, caught between the ancient and the present.

I let the stillness of the sacred courtyard wash over me, the faint scent of incense curling into the heavy, pine-scented air. I imagine myself adrift in the flow of history, a fleeting presence in a place where centuries have come and gone. In the vast cycle of samsara, I am just a traveller passing through: one ripple in an endless sea of existence, a swirl of consciousness lingering for a moment in the sensual world, before evaporating like a swirl of mist in a rainforest.