Twenty bridges from Tower to Kew

Wanted to know what the river knew.

For they were young, but the river was old,

And this is the tale the river told.

– Rudyard Kipling, The River’s Tale

Mid afternoon at Westminster Pier. The tide is making upstream with a steady urgency. Brown water laps at the pilings, dense and restless, whispering secrets I can’t quite hear. It shunts the pontoons of the pier back and forth against its pilings with a sonorous thump thump thump. Up on the Victoria Embankment, thousands of tourists are scurrying in the heat: cameras flashing, tempers flaring. Down here beside the river it is cool and shady.

A line from Rudyard Kipling’s poem The River’s Tale runs through my mind as I look out across the Thames: “Twenty bridges from Tower to Kew…” Kipling knew the Thames. In his day it was the river of Empire; a working waterway bristling with masts, cranes, and steamers, its tides thick with coal dust and commerce. The sun never set on the British Empire, and its heart pulsed through this tidal artery. Timber from Canada, tea from Assam, wool from New Zealand, and rum from the Indies all passed through the Pool of London beneath the silhouettes of cranes and chimney stacks.

Now, on this bright afternoon, the river feels less imperial and more introspective. County Hall stares sternly across the water, stripped of its bureaucratic power, its stone façade caught in a moment between past and reinvention. Sightseers queue nearby for the London Eye; souvenir stalls peddle plastic crowns and Thames snow globes. The river, as ever, watches it all without comment.

Yet beneath the churn of Uber boats and the gleam of riverside redevelopment, the old current still flows: its tides ebbing and flowing with memory and myth, as they always have.

The launch is a battered little motor cruiser called Cockney Sparrow,: or Sparra, as the skipper calls her. She’s squat, low in the water, and surprisingly cheerful. The tide’s still making as we cast off, and the river is alive with movement. Wakes crosshatch the surface like the strips from a cat-o-nine-tails. The current runs strong, muddied by tugs, tourist boats, and Thames Clippers that barrel past, indifferent to our smaller wake. The Sparra noses into the flow like a Londoner elbowing through rush-hour on the Tube: purposeful, compact, unbothered.

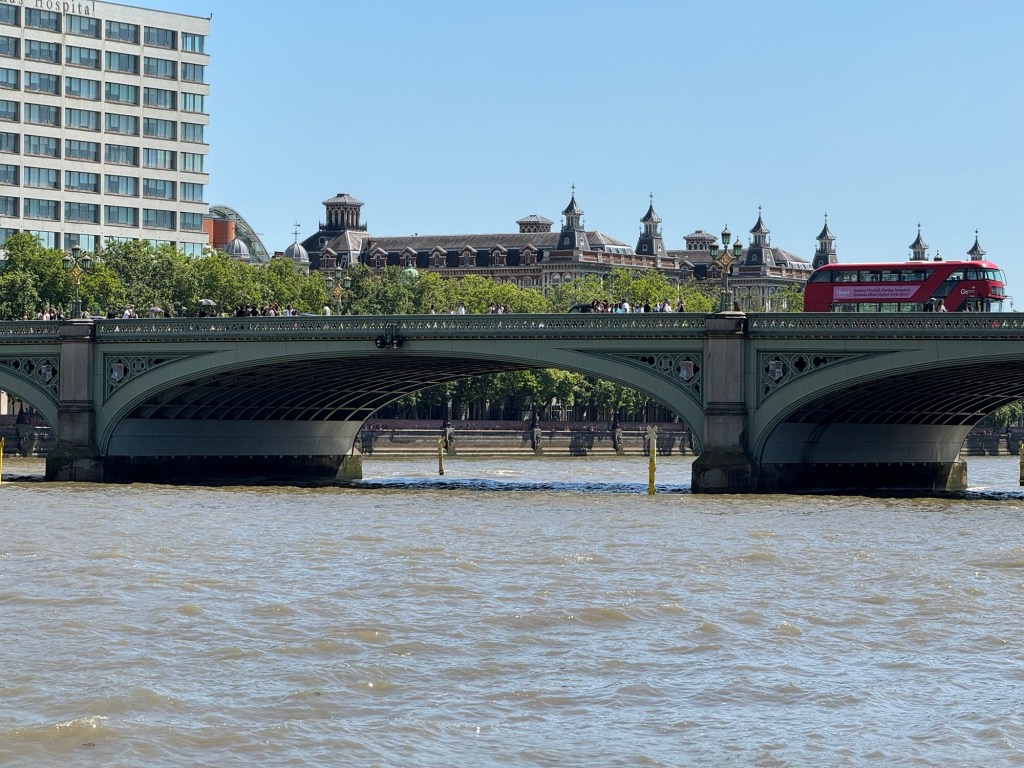

We pass under Westminster Bridge, and I glance up at the green iron ribs, the colour of Commons benches, supporting centuries of crossings. The current brushes its stone piers as it has since 1750, when the first bridge on this site broke the monopoly of London Bridge and scandalised the Thames Watermen. Today’s cast-iron version, opened in 1862, was designed by Thomas Page and adorned with Gothic details by Charles Barry: the same hand that designed the Palace of Westminster itself.

It was this bridge that inspired Wordsworth’s sonnet in 1802: “Earth has not anything to show more fair.” He wrote of a city clothed in morning light, still and silent, the Thames gliding at its own sweet will. That vision seems almost impossible now, but in rare moments, like this one, the echo lingers.

Downstream, I can see Hungerford Bridge and its pedestrian appendages, the Golden Jubilee Bridges, threading south London to the Strand. Cranes tilt and creak above the skyline: steeples of a newer faith, always building. London’s face is never still.

Vauxhall Bridge has a ribbed underbelly of rusting steel and grime-blackened trusses. From this low angle, the city’s polish disappears. The Cockney Sparra growls through the chop, and the wakes fan out behind us like a tattered pennant. Office towers glint, anonymous and aloof, but beneath the bridge the river is all muscle and oil, holding its breath between tides.

This is Joseph Conrad’s river: industrial, muscular, powerful. It heaves with the memory of merchant fleets, coal barges, imperial trade. The facades of Lambeth and Millbank are darkened by a century of soot, as if the very bricks remember the clank of chain and the stink of tar.

The monolith of Battersea Power Station squats on the southern shore, its iconic chimneys chalk-white against the sky. Once a cathedral of coal and current, it’s now been reborn as a retail playground: a temple of capital instead of carbon. But the bones of the place still murmur the past. I think of Animals by Pink Floyd: that brooding inflatable pig drifting above these same chimneys, part satire, part omen. Even scrubbed and polished, Battersea still snarls with the energy of its industrial youth.

But as we pass Battersea, something begins to shift. The river narrows, the banks edge closer, softened now by trees, houseboats, Georgian terraces. The sky opens wider. We leave behind the grimy grandeur of dockland London, and the Thames begins to daydream.

By the time we reach Putney, the tide has slackened. The river breathes more slowly here. Scullers slice through the surface like swallows; a cox’s voice echoes across the water: staccato commands, crisp and martial. This is Jerome K. Jerome’s river, a Thames of straw boaters, of sandwiches in wicker hampers and teacups balanced on the gunwales.

The Cockney Sparra putters along past Hammersmith, past Chiswick Mall with its prim front gardens and leaning fig trees, past the Duke’s Meadows where the river meanders in long loops. This is Ratty’s realm, the domain of slow afternoons and lazy punts, of riverside pubs named after swans and botanists. I half-expect to see Mole with a picnic basket on the bank.

I sit on the port-side bench, warm wood beneath me, and let the movement of the hull rock the day into memory. Central London is still somewhere behind us, ticking away behind cranes and glass and moments that make up another day. But up here, approaching Kew, the river returns to itself, a quieter, older self, free of ambition, heavy with reflection.

And still the Sparra chugs on, entering a realm where time eddies. Hammersmith Bridge appears ahead: an aging, green-lacquered suspension bridge with an air of theatrical decay. We drift beneath its twin gothic towers, the cast-iron cables overhead sagging like tired muscles. It can no longer carry traffic; it’s skeletal steel frame is too fragile for the weight of the present. Now it stands like a stage set for a Victorian drama, suspended in elegance and redundancy. Cyclists and pedestrians pick their way across it as if walking on a relic.

The engine throttles back, and the wake of the Sparra is soft now, merely a sigh along the hull. Barnes Railway Bridge approaches: the ironwork oxidised and brittle-looking, sun-dappled water flickering below. Here, the river no longer flexes. It glides.

Trees crowd both banks, and a little wooded island swells into view: Oliver’s Eyot (or as the skipper calls it, “Cromwell’s Island”) is a tangled pocket of wilderness in the middle of the Thames, supposedly once the headquarters of Oliver Cromwell during the Civil War. Now it’s the haunt of nesting birds and mystery. The current splits and swirls around it like a pilgrim bowing before a shrine.

We are far from Conrad now. This is the Thames of Edwardian outings, all water-meadows and whispered conversations, blazers and bunting, crustless sandwiches and clinking china. The buildings grow fewer. Trees take over. The river is no longer a corridor for trade but a stage for reverie. It is Wind in the Willows territory. Ratty would feel very much at home.

At Kew Bridge, the Sparra sidles up to the pier. The water is calm, almost still, like the end of a long breath. I step off the boat and glance back at the river. From Westminster to Kew, it has told a story in reverse: from empire to idyll, from steel to silt. The river knows. It always has.