The British Museum is chaos.

We arrive early to beat the rush; but there is no beating the rush. Thousands of people swarm through the Great Court, clicking photos, clutching guidebooks, trailing children and dragging backpacks. They move from room to room with glassy-eyed exhaustion, barely glancing at the Rosetta Stone, shuffling past the Parthenon marbles, murmuring half-remembered facts about Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt. Knowledge, it seems, is no longer something we seek: it is something we consume. And only for a second, before scrolling to the next thing.

I try to focus, but the din is overwhelming. Selfie sticks flick in and out like antennae. The air is thick with the sound of hundreds of conversations in dozens of languages, all merging into a dull roar. The rooms are vast but feel airless, heavy with too many objects and too little context. The museum, for all its grandeur, feels cluttered. Not just physically, but mentally. Nothing is allowed to breathe.

And then I find it.

Down a side corridor, past a weary-looking gallery assistant half-hidden behind a pillar, I step into a room and the noise disappears. The Enlightenment Gallery. Suddenly, I can breathe again.

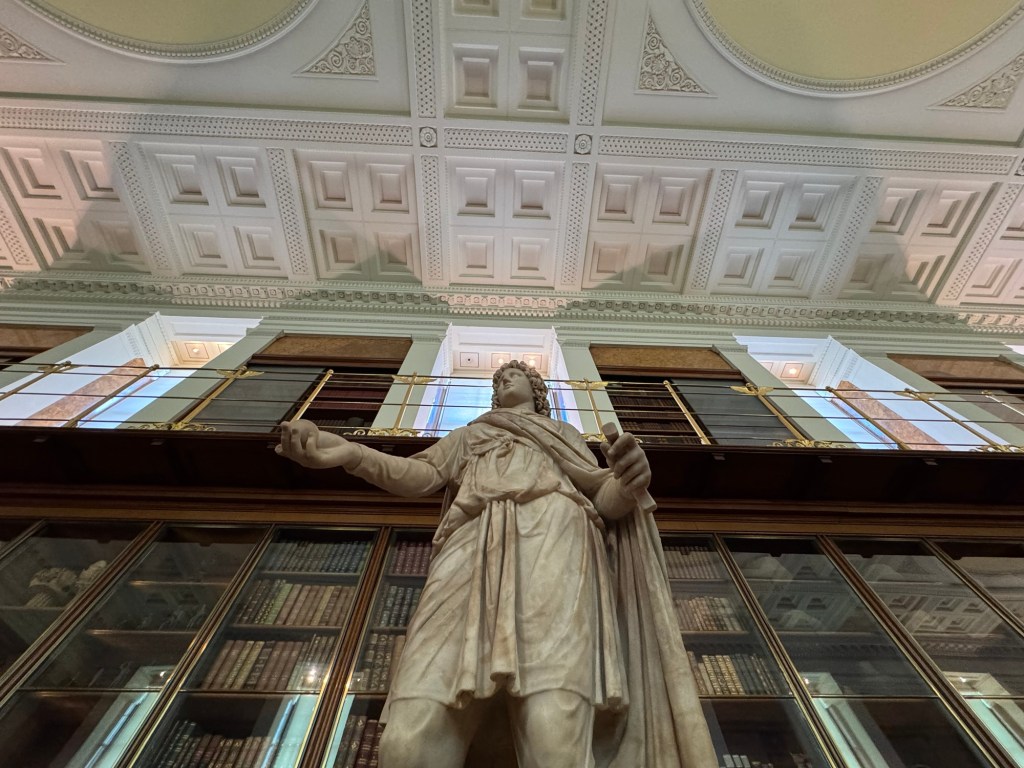

This is what a museum should be.

The room stretches out before me in elegant symmetry: long cabinets of glass and wood, oak bookcases stacked floor to ceiling with ancient tomes, sunlight filtering through tall windows and falling like spilled milk across the polished floor. Here are the tools of curiosity. Globes, fossils, surgical instruments. Astrolabes and chronometers. Coral specimens. Roman coins. A wooden case of pressed ferns labelled with meticulous copperplate handwriting.

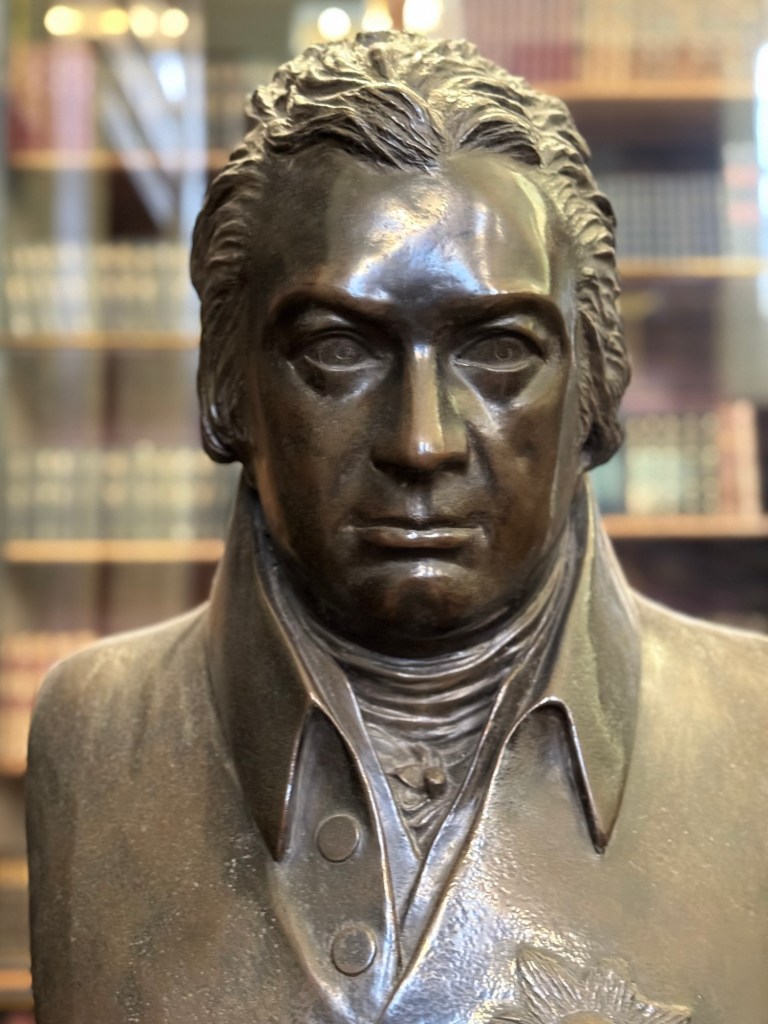

A bust of Joseph Banks looks out from one corner, stern and visionary. A little further along, a marble Hercules stands mid-snarl, his curls arranged in classical defiance. Near the centre of the room, carved from dark diorite and towering over the cases, stands Sekhmet: lioness-headed goddess of ancient Egypt. The patroness of war and healing. Her gaze is cool and commanding, her stillness magnetic. I find myself standing before her for a long time, unsure whether I am studying her or being studied in return.

In this room, knowledge is not background noise. It is the architecture. It lives in the arrangement of objects, in the handwritten labels, in the gentle reverence of the air.

This gallery was created in the age of the Enlightenment, a period that began in the late 17th century and burned with its brightest flame through the 18th. It was an era when Europe—particularly England—was seized by a new hunger for understanding. The world was no longer just God’s mysterious design; it was something to be measured, mapped, catalogued, dissected and discussed. Knowledge, previously confined to the pulpit or the palace, was now being pursued in coffee houses, drawing rooms, laboratories and libraries.

Men (and yes, it was mostly men, though a few remarkable women fought their way into the margins) devoted themselves to learning for its own sake. They were not experts. They were generalists in the best sense of the word: polymaths, amateurs, collectors, dreamers. They studied plants and poetry, stars and stones, bugs and bones. They wrote letters that travelled continents and took years to be answered. They joined societies. They drew diagrams. They devoted entire lives to compiling multi-volume sets that nobody read. They sought to understand the world: not to dominate it, but to be astonished by it.

And their collections—these trophies of curiosity—became the foundation of modern museums. Cabinets of curiosity grew into institutions. Drawers of shells and beetles became public exhibitions. Museums were no longer only about treasure. They became temples to human wonder.

But in this temple, the pilgrims seem weary.

Outside this gallery, most of the museum’s visitors wander without purpose. They check the time, glance at the maps, search for the nearest toilet. They squint at placards with tiny writing. They take pictures not of the artefacts but of themselves in front of the artefacts. This, too, is knowledge: but not the kind the Enlightenment thinkers imagined. This is performative knowledge. Knowledge as entertainment. Content.

A child walks past a 4,000-year-old Assyrian tablet, eyes fixed on a phone. A man in cargo shorts stands next to the bust of Sophocles and tells his partner, “That’s Plato, I think.” A group of teenagers sit cross-legged on the floor beneath a Grecian urn, scrolling their feeds. Nobody looks up.

But in here—in the quiet of the Enlightenment Gallery—I feel a different rhythm. It’s not nostalgia. It’s something deeper: a kind of recognition. A sense that this space was built by people who believed that ideas mattered. That a fossil, properly examined, could change how we understand the past. That a sculpture of a god could open a conversation about human purpose. That books—real books, written with ink and bound in leather—could be the scaffolding for a lifetime of thought.

I move slowly, reading labels, touching glass. I hold a 4,000 year old clay cone pressed with cuneiform. It’s a king’s decree from ancient Mesopotamia, a declaration of temple construction. I wonder about the hand that shaped it. What kind of tool did they use? Did they know they were leaving a message that would outlast their entire civilisation?

In one case, there’s a 17th-century microscope. In another, an orrery with tiny brass planets ticking endlessly around a miniature sun. Here is knowledge in its rawest form; not the knowledge of data and algorithms, but the knowledge of wonder. The kind that begins with a question and leads not to a conclusion, but to more questions.

I think of Joseph Banks, sailing with Captain Cook to the edges of the map, collecting plants and drawing birds, enduring storms and sickness in pursuit of something that could not be bought or sold: understanding. I think of Mary Anning, scouring the cliffs of Lyme Regis for fossils with her dog Tray, reshaping palaeontology without ever being allowed to join the societies her discoveries fed. I think of John Locke, whose mind wandered through philosophy the way Banks wandered through Tahiti.

They would weep, I suspect, to see their legacy reduced to a digital photo-op. And yet, this room remains. Untouched by the frenzy outside. A sanctuary. A whisper in a world of shouting.

I sit for a while on a wooden bench beneath the gaze of a Roman philosopher. A shaft of sunlight catches the spine of a book labelled Natural Histories of the Animal Kingdom. I close my eyes and breathe.

Out there, the museum is still a destination. But in here, it is still a journey.

I rise, nod to Sekhmet, and walk out into the brightness.