Morning in Cirencester. I step into the church vestibule, leaving the harsh summer sun for the cool shade of the nave. Inside, the architecture pulls me forward like a breath held too long. Here, in the Church of St John the Baptist, the vertical line announces itself not with flamboyance, but with intention. Arches rise in quiet ranks. Light filters through clear glass and tall windows. There is a sense of balance, of upward motion, of quiet order stretching toward heaven.

This beautiful church in the West Country is the beginning of my journey to understand English Perpendicular, a descendant of Gothic ecclesiastical architecture that evolved to suit a nation not given to the excesses of flamboyance.

Perpendicular Gothic emerged in the late 14th century and remained the dominant style of English ecclesiastical architecture until the early 16th. It is marked by clarity, logic, and verticality. Compared to the Decorated Gothic that preceded it—with its florid tracery, complex vaulting, and playful naturalism—Perpendicular is stern. Focused. It reduces the ornamental to amplify the structural.

The vertical line is more than just an architectural motif. In England, it is a theology. A philosophy. A prayer in limestone and Purbeck marble. It introduces vast window walls, rectilinear paneling, and vaulting that grows increasingly skeletal and abstract. It turns the church into a kind of philosophical diagram: lines moving ever upward, toward light.

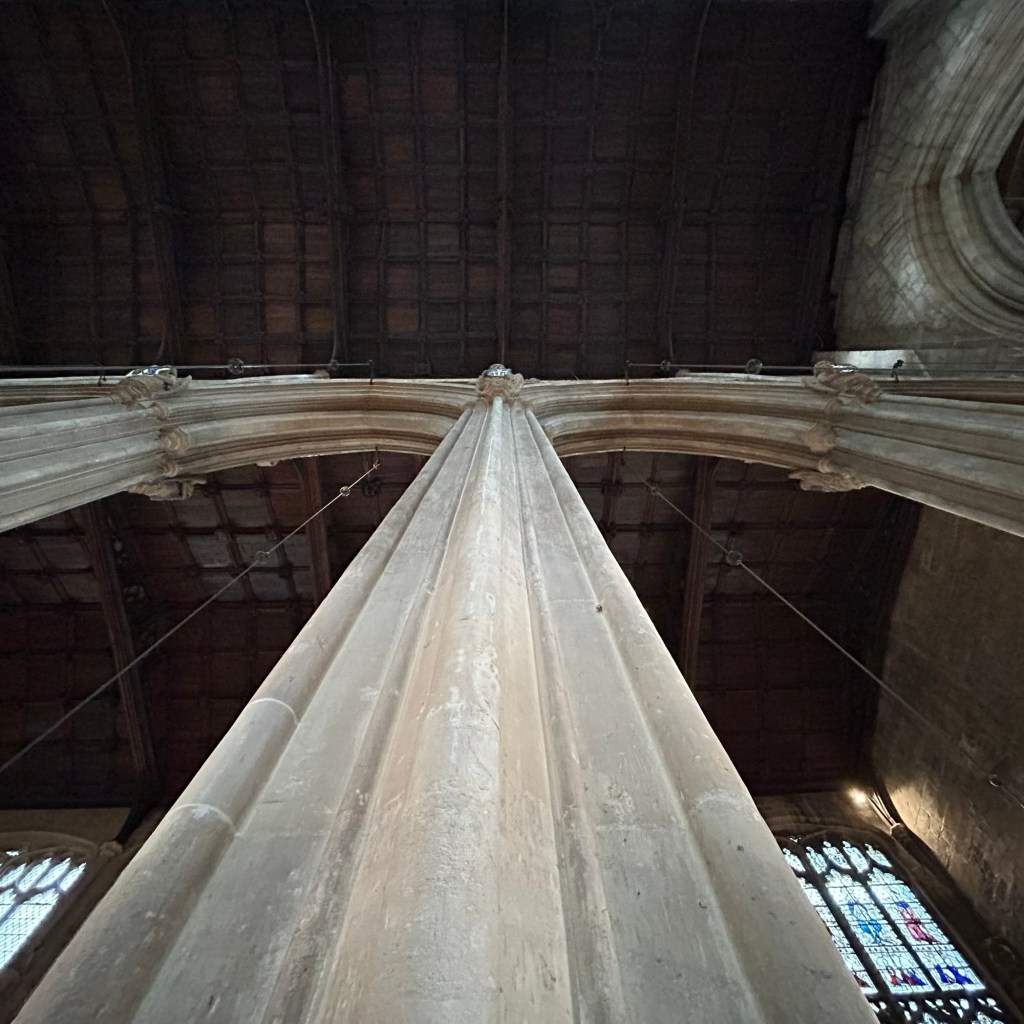

Here in Cirencester, I feel the early stirrings of that transition. The wooden ceiling is richly coffered, dark as a sailing ship’s timber. The arcades march rhythmically like a procession of monks. There is a sacred geometry in the space, a sense of calm calculation. The kind of structure where belief becomes embodied in stone.

I look up and feel something uncoil in my chest. This is architecture as aspiration. And something in me is already rising with it.

Bath is a city that wears its beauty on the surface: golden facades, Georgian crescents, Roman echoes. But I’m not here for symmetry or hot springs. I’m here for the spire.

I find it near the Abbey, rising into an impossibly blue sky. At first glance, the spire seems insubstantial. Light pierces it from all sides. Its base is a lantern: eight-sided, open, delicately buttressed. It looks like it might simply float away. I walk around it slowly. The tracery is so fine it seems woven. Through its open arches I can see gulls, sky, the sun winking off the weathervane.

This is where the Perpendicular style becomes almost ethereal. A stage in the pilgrimage where mass begins to dissolve. Where the vertical line no longer carries the full burden of weight. Instead, it begins to point. To suggest. To whisper rather than insist.

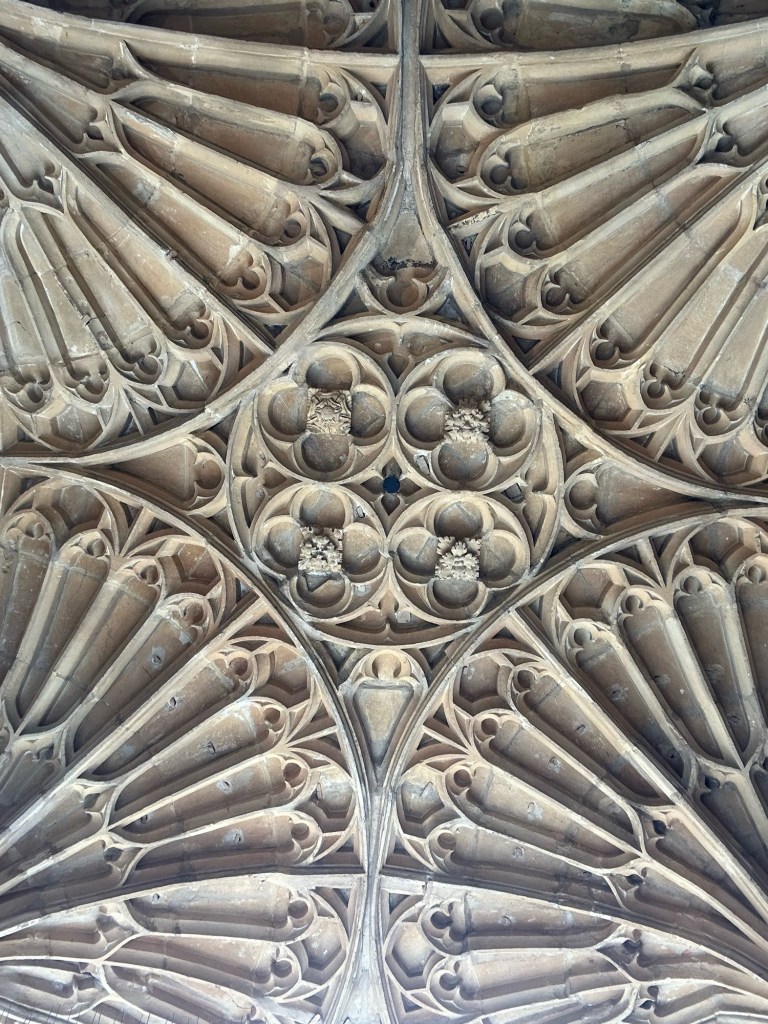

Inside Bath Abbey, the line becomes lace. I step beneath the fan vaulting and feel the space open like a flower. Stone ribs bloom from slender columns, spreading outward and upward like the pleats of a royal cape or the branches of some sacred tree. There is grace here. Intentional lightness.

And yet, the control remains. The whole space is perfectly ordered, symmetrical, coherent. It is as if Perpendicular Gothic, after centuries of self-confidence, has allowed itself a moment of lyricism. A flight.

Light pours in through the massive east window: glass panes of story and colour. Saints, kings, symbols, all rendered in deep reds and ultramarine. But even the glass bows to the architecture: rectangular panels, strict verticals, no chaos.

I sit in a side aisle for a long time, just watching how the light moves across the ribs. The fan vaulting overhead is not just decoration—it’s metaphysics. It reveals a world where everything rises and radiates from a single point. Where space itself is an act of devotion.

And so, at last, I arrive in Salisbury. It is morning again. The sky is mottled pewter and the spire disappears into it: the tallest in England, a tapering dagger of belief. At 404 feet, it is not merely the apotheosis of the Perpendicular: it is its final, perfect note. The vertical line has now become not just architecture, but the architecture of aspiration.

I step inside and the space engulfs me in silence. The nave stretches away like a nave should: long, tall, perfectly proportioned. Here, the Perpendicular has reached its final refinement. There is no flamboyance. No flourish. Just line. Order. Stillness.

I walk slowly beneath the vaulting, pausing beneath the tower to look up. The ceiling here is a marvel of engineering. Ribs. Gold struts. Geometry as worship. At its centre, a dark void: the opening of the tower above. I feel the pull of it in my bones, a slow, gravitational yearning.

In the centre of the cathedral, a mirror of black water reflects the whole nave in perfect reverse. Columns, vaults, tourists: all mirrored in darkness. I lean over the edge and see myself, floating there among the arches. A pilgrim in a world designed to point past the self.

Everywhere, the rhythm of the space continues: pointed arch upon pointed arch, bays defined by slender piers of pale stone, light filtering through tall windows without interference. Compared to the richness of Bath Abbey, this feels austere. But in that austerity, I find peace.

Perpendicular is not just a style. It is the architectural expression of a theological idea: that to rise is to believe. That height is holiness. That light, ordered by line, is grace.

It says: truth is found in clarity. That form can carry meaning. That the space we inhabit shapes the thoughts we have. English architects didn’t just build big churches. They built philosophies. They built diagrams of heaven. Blueprints of salvation.

And even now, centuries later, I can feel it. In Cirencester’s wooden ceiling. In Bath’s fanned vaults. In Salisbury’s silent heights. The vertical line is not about grandeur. It’s about attention. About reaching.

I walk back out into the Wiltshire air and look up at the spire one last time. The line continues.