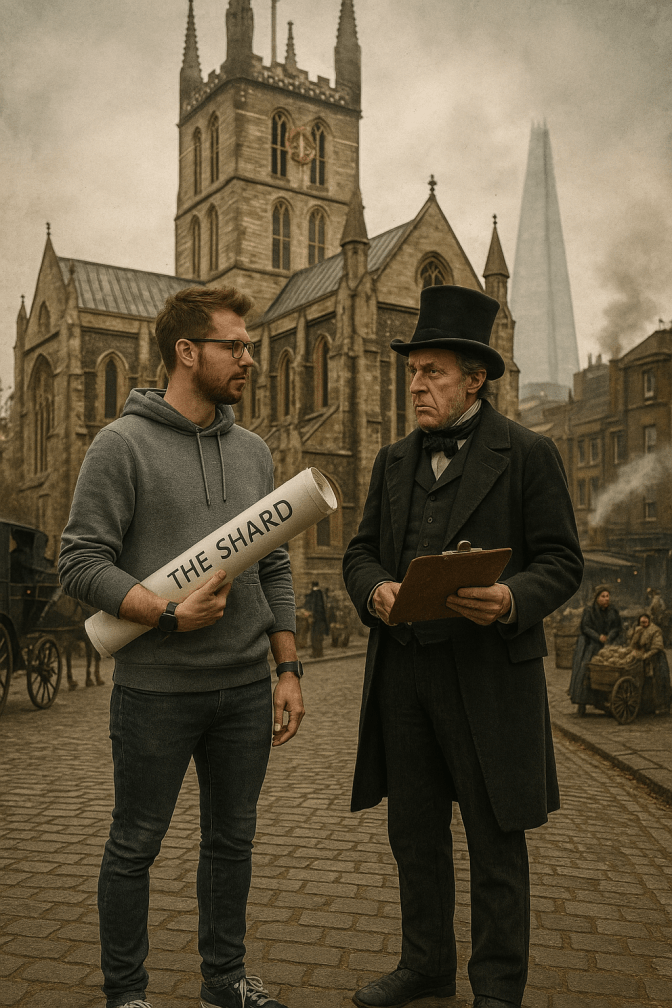

(As Presented to the Esteemed Mr. P. Throckmorton, Town Planner, London Borough Council, 1889)

Good morning, sir. Allow me to introduce myself. I’m the appointed Project Manager for The Shard, a mixed-use vertical city block that will reimagine the London skyline. Yes, vertical. We are going up, way up, and we’re taking London with us.

Picture this: a single structure soaring 310 metres above Southwark, like the spire of your finest cathedral, only multiplied severalfold. Think Salisbury Cathedral meets the Crystal Palace Exhibition… after a brisk session with Mr. Eiffel.

Core proposition:

We condense what you spread across a dozen soot-stained blocks— offices, restaurants, observation galleries, luxury residences—into one elegant spear of steel and glass. Imagine the efficiency, sir. No more trudging through pea-soup fog from the Post Office to the tea rooms; in The Shard, you simply change floors.

Architectural USP:

We’re crafting this as an icon. The Shard will not merely be a building; it will be a navigational landmark, a civic statement. Ships entering the Pool of London will see it gleaming like a shaft of morning light. From Greenwich to Kew, from Hampstead Heath to Sydenham Hill, The Shard will whisper: You are in the heart of the capital.

Public value proposition:

At its apex, a viewing gallery will allow citizens to survey their Empire in miniature. Stand at the top and behold: the meandering Thames like a silver artery; Westminster Palace gleaming with political resolve; St Paul’s dome receding to a mere thimble on the skyline. It’s civic pride distilled into an experience, and, dare I say, a fine sixpence admission fee.

Engineering credibility:

Sir, I have, in my day, had dinner with the real Project Manager of The Shard—in Lydiard Millicent, of all places—and I can assure you the logistics are sound. Our lifts ascend faster than your Brighton Express. The structure’s bones are steel; its skin, glass; its spirit, unflinching ambition.

In short, we are not just constructing a building. We are building London’s future. A vertical city in the clouds, rooted beside the ancient stones of Southwark Cathedral, a fusion of your age’s permanence and ours’ audacity.

Shall I send you the tender documents?

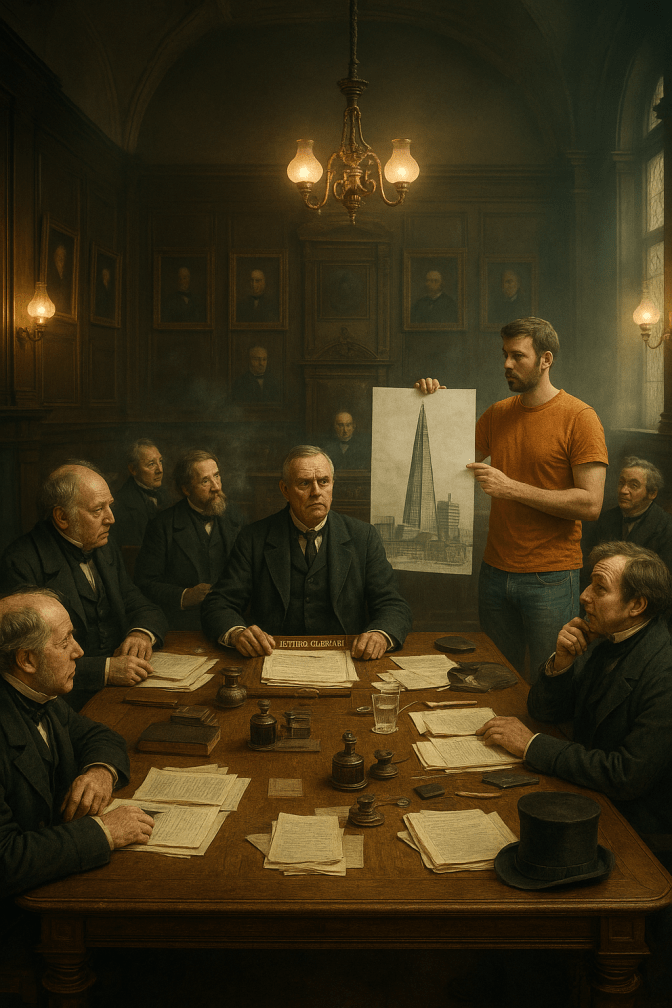

Minutes of the Southwark Borough Council, Town Planning Committee

Dated this 14th Day of October, 1889

Subject: Presentation by Mr. F. [Name withheld for brevity] on “The Shard”

Attendance:

Mr. P. Throckmorton (Chair)

Alderman Wetherby (Vice-Chair)

Councillors Bloggs, Hinchcliffe, McTavish, and Snipe

Clerk to the Council, Mr. Wills

Proceedings:

- Introduction:

The Committee received Mr. F., who professes to be a “Project Manager” from the year 2025, and who claims acquaintance with the “real Project Manager” of said work, having taken dinner with him in a Wiltshire village of unremarkable note. - Proposal Summary:

Mr. F. proposes the erection of a singular edifice of “glass and steel” to a height of over one thousand feet. This structure, named “The Shard,” is intended to accommodate commercial offices, eating-houses, private dwellings, and an elevated public gallery affording views over the Metropolis.

Note: The Committee expressed doubts as to the safety of placing the public at such an altitude, fearing windburn, lightning strikes, and existential dread. - Public Benefit:

The Proponent assures that “citizens may survey their Empire in miniature” from the uppermost storey, and that the admission fee could be “sixpence.” Councillor McTavish opined that sixpence is better spent on a pint of mild ale and a meat pie. - Engineering Concerns:

Mr. F. describes “lifts” capable of rising faster than an express train to Brighton. The Chair questioned the wisdom of trapping paying customers in a small box and firing them skywards at such velocity. Councillor Snipe feared the contraption might “dislodge their vital humours.” - Architectural Considerations:

The Proponent likens the work to “Salisbury Cathedral meets the Crystal Palace Exhibition after a brisk session with Mr. Eiffel.” The Chair found this “at once flattering and deeply troubling.” - Conclusion:

The Committee is of the opinion that Mr. F. is a gentleman of vivid imagination and robust hospitality (owing to his convivial Wiltshire dinner anecdotes) but that his proposal constitutes:- A danger to aviation (should any such craft ever exist)

- A hazard to the public peace (from the shock of beholding it)

- An affront to local chimney sweeps, who would be rendered unemployed by the lack of chimneys on such a structure

Resolution:

That the proposal for “The Shard” be tabled until such time as:

(a) London is free of fog

(b) Building to the heavens is deemed a respectable pastime

(c) The Empire learns to enjoy its views from street level

The meeting adjourned at 5:43 p.m., following the consumption of seed cake and a round of restorative port.

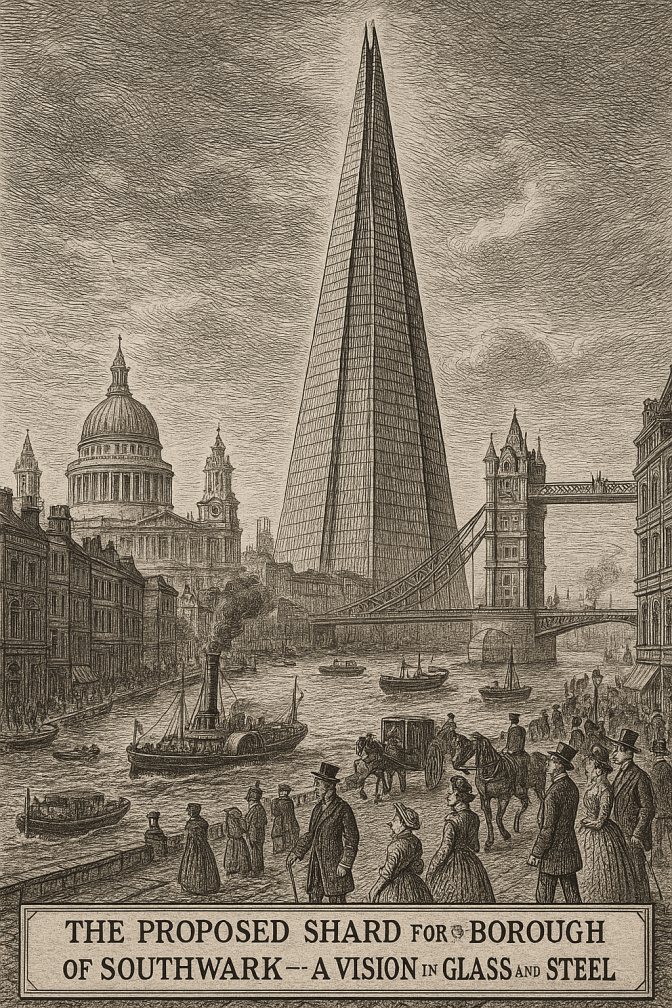

The Illustrated London News

Saturday, October 19th, 1889

A TOWER FOR THE SKIES:

BOLD SCHEME TO RAISE SOUTHWARK INTO THE CLOUDS

Our readers will be astonished — and, we dare say, divided — to learn of a remarkable proposition lately brought before the Southwark Borough Council. In a meeting this past week, the Committee on Town Planning was addressed by a gentleman identifying himself only as “Mr. F., Project Manager, Year of Our Lord 2025.”

The gentleman, attired in a most peculiar blend of colonial tweed and what was described as “poly-technical footwear,” spoke at length of an edifice he styles The Shard — a colossal spear of steel and glass to ascend far above even the tallest steeple of the Metropolis. Its height, we are told, will exceed that of St. Paul’s Cathedral nearly threefold, and from its uppermost galleries one might discern, on a clear day, the white cliffs of Kent and, perhaps, the blush of France.

The structure, according to its advocate, will contain within itself a compendium of London life: offices for mercantile clerks, eating-houses of diverse quality, drawing-rooms for the wealthy, and a public gallery from which the view would be “worth a thousand sermons.” An entry charge of sixpence was mooted, though one alderman countered that the sight of the Borough from so great an altitude would cause any respectable citizen to faint away, rendering the investment unprofitable.

Our artist, having consulted with the proposer, has furnished the accompanying engraving (see Fig. 1) which depicts The Shard as it might appear, should the scheme proceed. In the image, the tower rises like a frozen bolt of lightning above the Thames, dwarfing St. Paul’s to a bauble and making a plaything of Tower Bridge. The dome of the Cathedral appears as the lid of a pepper pot in its shade, while omnibuses, reduced to the scale of clockwork toys, ply the roads below.

Local Reaction:

Opinion in Southwark is mixed. A fishmonger on Borough High Street declared it “an abomination” which would “block the sun from my mackerel.” A chimney sweep, more sanguine, remarked that if gentlemen were to spend their afternoons peering from glass palaces in the clouds, they might at last leave their chimneys in peace.

The Council’s Verdict:

The Borough Council, after due deliberation, resolved to table the matter indefinitely, citing concerns that the structure might interfere with migratory birds, celestial navigation, and the Almighty’s view of His own creation.

Until such time as London sheds her fogs, broadens her horizons, and masters the art of propelling her citizens skyward without loss of hat or cravat, it seems The Shard must remain in the realm of fantasy — or, as our mysterious Mr. F. would have it, in the year 2025.

The Shard

The glass blade of The Shard glitters above me, slicing into a flawless July sky. From street level, its steel ribs and glass facets look impossibly steep, tapering into a vanishing point so sharp it could pierce flesh. I pause beneath its mirrored flank, framed by the leaves of a London plane tree, and feel the familiar Southwark hum: the rattle of trains, the cries from Borough Market, the old bones of the city pressed up against this gleaming newcomer.

Inside, the air is cool and hushed. The lift awaits like like a real-life Tardis, poised to take us to another point in quantum time. A soft chime, a rush of acceleration, and the city begins to fall away. The numbers climb faster than my ears can adjust. There’s a sense of leaving the horizontal world entirely, as if the lift isn’t so much moving as translating us into another dimension.

The doors slide open, and London floods in from every side. I step to the glass and look east: the Thames bends in a wide, pewter arc, the Isle of Dogs crowded with glass towers, the sinuous ribbon of railway tracks unfurling towards Kent. My reflection hovers over the city, ghostlike, as if I could step through and walk on the roofs.

Northwards, the City’s skyscrapers thrust upwards like a steel mountain range. The Walkie Talkie bulges over the river; the Gherkin gleams in the sun. Below, HMS Belfast lies at permanent anchor, her grey flanks casting shadows into the brown churn of the Thames. Riverboats carve white grooves on the water in every direction: a choreography of wakes and currents.

Up here, sound is absent. London’s roar has been turned to a slow pulse. Streets are mere lines between blocks of ochre and slate; parks are green pauses in the sprawl. The longer I look, the more I feel unmoored, as if I’ve slipped free from the grip of the city.

One final stairway carries us to the open-air platform. There’s nothing now between me and the sky but angled glass and the occasional gull riding the thermals. I crane upwards. The steel apex is impossibly far away, the last few metres of the building as unreachable as the stratosphere.

But drinks are being served—a Coke for me, bubbles for Linda and Lydia— and there are selfies to take. After all, this is what the modern public demands: proof of presence, tokens of altitude. Somewhere far below, in an imagined committee room wreathed in pipe smoke, I can almost hear Chairman Throckmorton and his fellow aldermen harrumphing into their ledgers, still unconvinced that any respectable citizen would pay sixpence to stand in the clouds. Yet here we are, glasses raised, London spread beneath our feet, fulfilling a future they could never have planned for, but one they might, in some grudging, gaslit way, admire.

From Southwark’s stones to this altitude, we have travelled centuries in minutes: from the gothic solidity of the cathedral to a twenty-first-century spear of ambition. I rest a hand on the glass and take in the world’s most familiar city, made strange by height and distance.

It is both London and not-London. And we are both here and, impossibly, somewhere above it all.