Among these dark Satanic mills…

– William Blake, Jerusalem

Deep beneath London, the Elizabeth Line train sweeps silently along its tunnel. At this hour, the carriage is almost empty. I feel like a traveller in space and time: alone in a linear void of speeding lights and static reflections. Encased in the halo of sound from my earbuds, I look at my reflection in the window opposite. My face, lit from above, looks like an automaton. The train sweeps beneath the Thames, bending like space-time under Nine Elms and glides to a stop at Battersea.

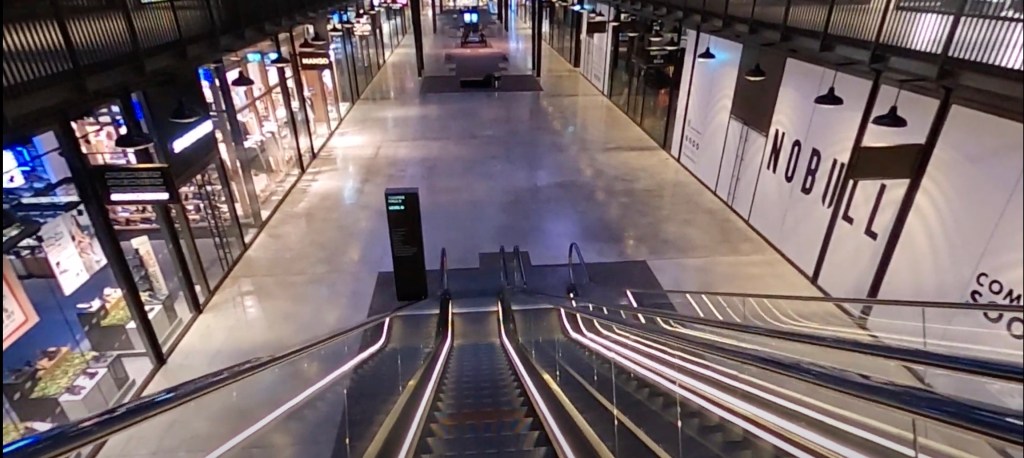

The doors of the train slide open with an elegant hiss. A disembodied female voice intones: “Please mind the gap.” I ride a gleaming escalator up to ground level, ascending from the brightly-lit, tiled space of the station towards the gloom of the outside world.

Another door slides open and I step out into the domain of titans. The brick colossus of Battersea Power Station rears before me. Its perpendicular walls, angular and vast, buttress two chimneys of pure white, propped against the sky. A sweep of steel and glass apartments curves away to my left, reflecting and transforming the symmetrical lines of the power station. The reflections twist and distort the building: a surreal dance of brick, concrete and steel across a canvas of sleek, modern glass.

…Battersea’s soul sighs.

A few early commuters and a handful of joggers inhabit the space between the lower walls of the power station and the shimmering bases of the apartments. I feel puny and overpowered by the grim, unyielding presence of the power station. Yet I am also captivated by its industrial gravitas. I feel it drawing me in, pulled by the raw, electric might that still seems to hum from the long-dead dynamos that once whirled within. I turn left and begin to walk.

It had been an easy transition from the benign to the stupendous. I had let myself out of my friend’s house in Notting Hill and stepped down onto the street. The grey sky threatened rain but I could see patches of blue, framed by the London plane trees growing along the pavement, promising a fine day to come.

I had walked to Westbourne Park station, ridden the District Line for two stops to Paddington, and then descended to the deep tunnels of the Elizabeth Line. Now, I stand in the shadow of the power station. It is at once both malevolent and utterly compelling.

I cross the circular accessway (“street” is far too grand a name for it) to the base of the building. It rears above me in perfect perpendicularity. I reach out and put my hand on one of the building’s six million bricks. I imagine the workmen who placed them there ninety years before. I hear the scrape of their trowels and the cries of the hoddies as they lugged their loads (12 bricks at a time) to the waiting brickies: “To rise in the world he carried a hod.”

A door is set into the north wall of the power station. Beyond it, a passage decorated with red chevrons on a white background leads to the machine hall, where the steam turbo turbine generators once sang their songs of power. In its modern incarnation, it feels cold and clinical, with brushed steel handrails and acres of glass: a latter-day Valhalla awaiting the arrival of the Gods.

Sleek elevators connect the mezzanine floors where exclusive emporiums — Apple, Armani, Under Armour — are yet to open. The notes of soft, electronic music hang in the air, unresolved. At this hour, the gigantic space is empty.

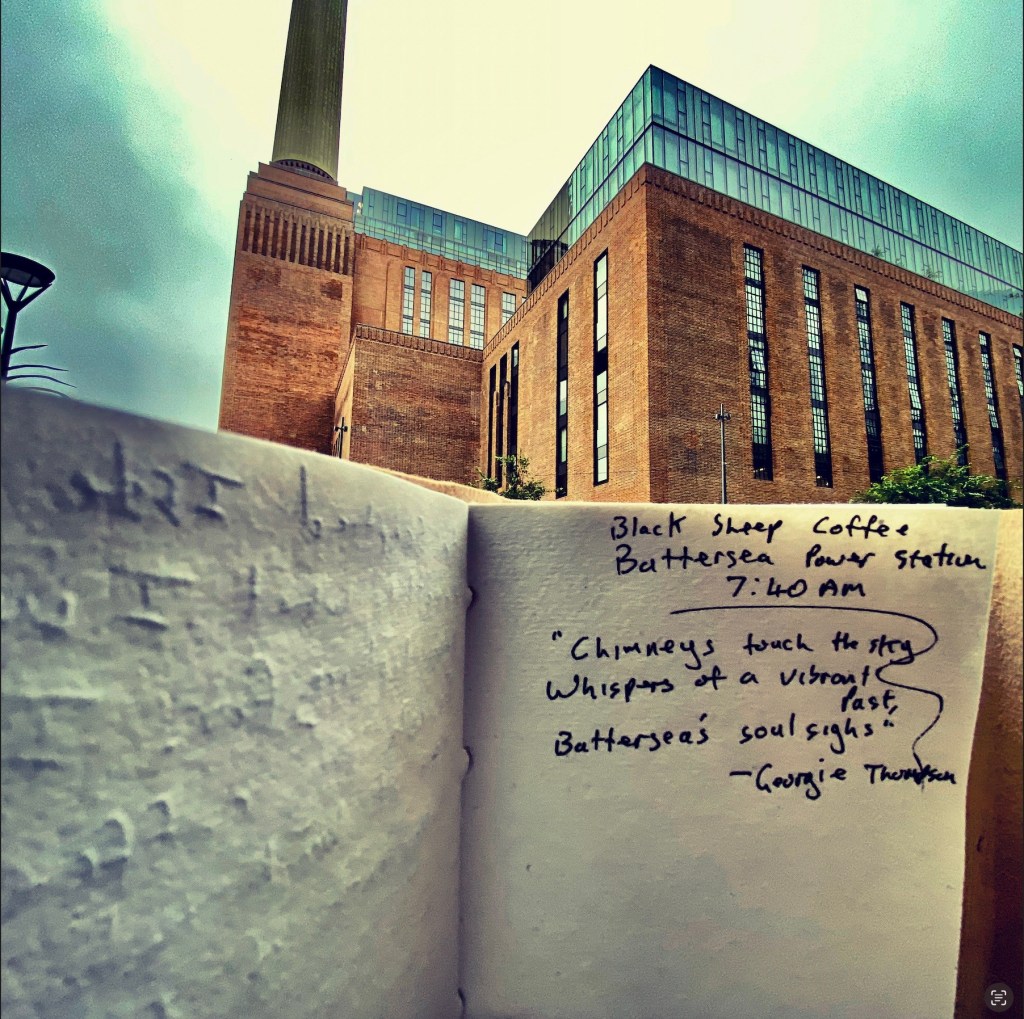

Back outside, I find a Black Sheep Coffee joint opposite the north-eastern corner of the power station. I order an oat milk latte and sit at a powder-coated table of black steel topped with faux marble. My wide-angle Instagram post can barely fit the coffee and the building in its frame. I ask my digital assistant, Georgie, to compose a haiku. She writes:

Chimneys touch the sky

Whispers of a vibrant past

Battersea’s soul sighs.

On the bank of the River Thames, where the coal barges endlessly delivered their black loads to be fed into the engulfing maw of the power station’s furnaces, a whimsical spread of bright green fake grass now lies. Topiary hedges and oversized seats add an Edward Scissorhands-style incongruity to the sinister bulk of the building rearing above.

A sprint track and spaces for games are marked on the grass. A podium for the winners in the events at the Battersea Games stands at the foot of the steps leading to the main entrance. It is a picture of surreal harmony: the garish hues of the grass and rows of deck chairs set against the imposing industrial backdrop.

…like an ancient guardian protecting a colossal secret.

As I cross the lawn, it occurs to me that this incongruity, where the whimsical and the industrial coexist, seems to be a reflection of the wider city, where the past is not erased but rather incorporated into the present in unique and imaginative ways. The power station, once a symbol of industrial strength has become a canvas for modern artistic and recreational expression. Despite the jarring disparity of themes, the scene before me in some way fits into the broader narrative of London: endlessly reimagined and reinvented over the centuries in eclectic and often eccentric ways.

In the centre of the lawn, I slip and fall. Intent on the image on the screen of my GoPro, I don’t see the slick grey tiles forming a lateral path across the grass. As I pick myself up, I think of Algie, the giant pig on the cover of the Pink Floyd album Animals. He, too, had suffered an ignoble fate during the production of the album artwork.

Conceived by the group’s bassist, Roger Waters, the cover art features a pink inflatable pig flying over the power station’s chimneys. Algie, however, had other ideas. His tether ropes parted during the photoshoot and he drifted away, gently sailing across the rooftops and spires of London before crash-landing in a Kentish field.

Two men in suits stand outside the doors of the North Entrance.

“Did you see that?” I ask. They look blankly at me, so I continue.

“If you fall over and nobody sees, it didn’t happen.”

Travel is all about these moments of levity. Feeling human again, I step once more into the Machine Hall. It is still empty. The elevators glide silently. The same electronic music plays: layered synth strings and filtered harmonics. The cavernous space rears above me. Pieces of restored machinery stand glowering from the heights.

My lighthearted mood instantly evaporates, replaced by a sense of awe and unease. The space feels inhuman, devoid of warmth and with an inimical sense of foreboding. I feel a deep longing to escape the city: to swap the tight, constricted spaces of London, epitomised by this soundless and soulless hall, for the clean air and light, the scent of ploughlands, the chatter of rooks and the open skies of Gloucestershire, my next destination.

The building, even with its industrial might now silent and cold, seems to be watching me, like an ancient guardian protecting a colossal secret. I hear a disembodied voice, purely imagined but still seemingly real, invoke the lines from another Pink Floyd song: “Welcome, my son. Welcome to the machine.”