I had my own compartment – plenty of space, plenty of provisions, the grapes, cookies, chocolates and tea that made being on the Trans-Siberian like a luxurious form of convalescence.

– Paul Theroux, Riding the Iron Rooster

Morning at Christchurch Railway Station. Frost on the windscreens of parked cars; a crackle of leaves underfoot. At this hour, 06:30, it is still dark. A few of the brightest stars still shine in the pre-dawn sky. The lights of the station cast long shadows across the forecourt.

I collect my ticket from the counter — Seat 7B — and then await the boarding call. It comes over the tannoy at 06:50. I walk down the platform to the far end of the train and take a photo with my phone looking back up the platform with the train standing poised for departure. Inside the carriage, it is warm and quiet. The sun is lightening the eastern sky above the city skyline. At precisely 07:00 the train begins to move. It glides effortlessly out of the station, around a sweeping left-hand bend, across Riccarton Road, and north through Merivale and Papanui along its silver lines.

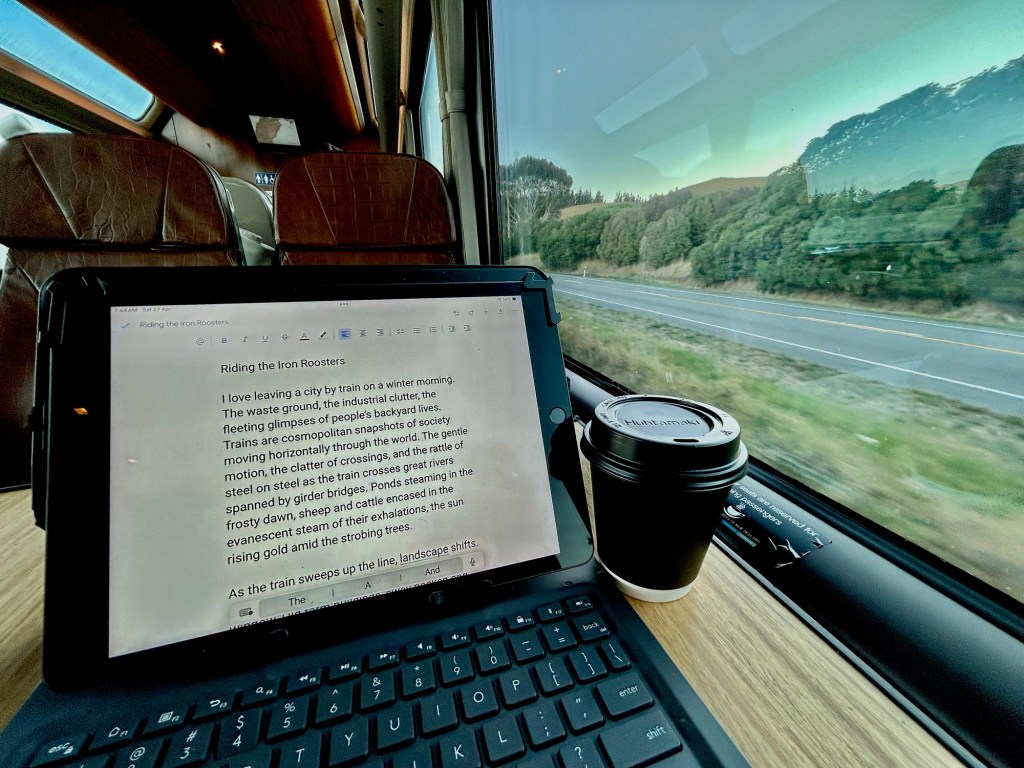

I love leaving a city by train on a winter morning. The waste ground, the industrial clutter, the fleeting glimpses of people’s backyard lives. Trains are cosmopolitan snapshots of society moving horizontally through the world. The gentle motion, the clatter of crossings, and the rattle of steel on steel as the train crosses great rivers spanned by girder bridges. Ponds steaming in the frosty dawn, sheep and cattle encased in the evanescent steam of their exhalations, the sun rising gold amid the strobing trees.

As the train sweeps up the line, the landscape shifts. So does the tableau spooling past outside my window. Old farm buildings, sway-backed and weathered, hunker against the cold. Occasional factory chimneys puff like tired sentinels. The city’s distant towers shrink, swallowed by the countryside.

Inside the cafe carriage, the scent of coffee mingles with the murmur of hushed conversations. The café attendant is having a break, eating toast, and scrolling her phone. Her long fingernails tap tap tap on the screen. Outside, in tiny towns and rural localities, people are beginning their day. The ventilation system brings in the occasional waft of woodsmoke and fallen leaves. The sun, still low on the horizon, casts long shadows across the folds of the hills and the wrinkles of the river valleys. It shines on the bow-string fences and glitters on the frost of shady hollows.

In his book Riding the Iron Rooster, the American travel writer Paul Theroux described train travel as “a luxurious form of convalescence.” His travel stories The Great Railway Bazaar, The Happy Isles of Oceania, and Riding the Iron Rooster were inspirational in my becoming a travel writer. And sitting here in the enveloping warmth of the train’s cafe car, surrounded by luxurious food and drink I, too, feel as though I’m convalescing, with nothing but my reflection in the big window for company.

The line crosses and re-crosses the main highway, where grim-faced drivers are held back by barrier arms and clanging ganger bells. A bull climbs a cutting of yellow clay. A flock of ewes flee the sound of the train across a broad paddock of brown top grass. The train slows as it climbs an incline through a forest of dead poplars, their bark silver-gray against the sky.

The line describes a long curve into Scargill then meanders down a long river valley. The line echoes the braids of the river, bending left and right along its southern bank. We cross a bridge high above the water and pass through hills clad with neat forests of conifers. The effects of the long summer drought are still burned into the parched landscape south of Cheviot; at Parnassus — named after the mountain home of Apollo and the Muses — irrigation has made the farmland green and fecund. The train climbs another incline at Fernihurst, passes through the gorges of the Conway River, and then descends to the Pacific coast.

The transition is sudden and striking. Emerging from the ragged confines of the ranges, the sky bursts open into a world of blue. The line hugs the very edge of the ocean, which dumps heavy white breakers onto the black sand beach with an audible thump. Seals bask on the skeins of black rock protruding from the water and loll in droves amongst the flax and foliage above the tide line.

The line passes through a series of tunnels. The highway is right beside the line and truckers wave at the passengers standing in the open observation deck. The ocean shimmers in the sunlight. Offshore, hidden beneath thousands of metres of water, the Hikurangi Trench funnels cold, nutrient-rich currents up to the surface. New Zealand fur seals, several species of whales, dolphins, and a plethora of pelagic birds thrive in these waters which have been described as “an underwater Serengeti.” Whale-watching aircraft turn in the sky overhead; a flotilla of cray fishing boats patrol their fishing grounds.

North of Kaikoura, the train speeds along the narrow littoral between the ocean and the ranges. Shaggy-coated horses graze in tiny gorsy paddocks. Fields of golden tussock sway to the sea breeze along the dunes. Surfers ride the lines at Hapuku beneath the gaunt, shingle ramparts of the Seaward Kaikoura Ranges which drop sheer to the ocean.

A fine mesh of sea haze clings to the lower edges of the mountains. The forest has been combed flat by the prevailing winds. The train passes through another series of tunnels, dark and echoing. The coastline is jagged, with fangs of rock breaking up the swells into swirls of white. Before the 2016 earthquake, many of these reefs were underwater. Now, they are part of the land, inching slowly upwards as the tectonic plates push and pull. The rocks above the high tide line are bleached white with the remains of marine vegetation that once grew beneath the water.

Beyond Kekerengu, the black sand beach extends northwards to the horizon. Between the railway line and the dunes, undulating fields of russet and gold tussock contrast sharply with the bright blue of the ocean. Scrawny, dog-eared sheep graze the coarse, salty grasses of scrubby fields bisected by ramshackle fences.

At the northern end of the Kaikoura Coast, an echelon of turbines turns ponderously in the breeze, taking the kinetic energy of the wind and converting it to electricity. The line turns westwards into a landscape riven by fault lines and rumpled by the thrust and slip of tectonics. Here at the top end of the South Island — the North Island is just visible across Cook Strait — the Alpine Fault has brought together rocks of many different kinds. Limestone outcrops are smashed together with mudstone and shales. The hills resemble the rumpled folds of a thin, ragged rug pushed up against a broken wall and covered with a skin of wind-blown clay. Drought has burned the Wither Hills to the colour of bone.

Neat rows of grape vines are stitched into the fertile river flats on the approaches to Blenheim. The vines are crimson and yellow with autumn foliage. The train click-clacks into the station and I disembark. As I walk out onto the street, I hear the train whistle blow as it begins the final stretch of its journey along the silver lines.