Returning to China after thirty years, following in the footsteps of my great uncle, I find both the country, and myself, completely transformed.

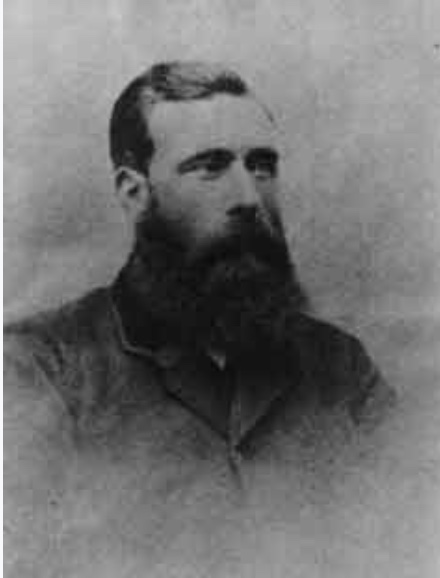

With the following paragraphs, my great uncle, the soldier, explorer and ornithologist Thomas Wright Blakiston introduced readers of his book, Five Months on the Yang-Tsze, to Shanghai and the Yangtze River:

“Deep in mud and deluged with rain, Shanghai hardly presented on the 11th of February, 1861, an appearance to justify the appellation of “The Model Settlement,” which it, nevertheless, so well merits in the far East. Its princely mercantile residences and extensive Consular buildings looked desolate and dripping. The “Bund” — that promenade of which the residents may well be proud — was deserted, save by a chance pair or two of coolies trotting along under heavy burdens, with their monotonous “ho-ha, eh-ho.”

“The Chinese city was but dimly visible beyond the forest of junk-masts above the foreign shipping,” he continues. “And one would have almost doubted that an immense mass of human life existed at all in the dismal scene, but for occasional explosions of crackers, with which the natives were propitiating the New Year, or “chin-chinning joss,” as it is familiarly called, for it was the second day of the first moon and holiday-time among the Celestials.

“But on the river, notwithstanding the incessant rain, there were signs of movement apparent among the vessels of war lately arrived from the Gulf of Pecheli; and during the day one by one they dropped down stream, forming by evening a respectable little fleet at Woosung.

“By nine on the following morning Vice-Admiral Sir James Hope* had assembled his squadron outside the mouth of the Woosung or Shanghai river; and at ten, each vessel being in its allotted position, the Expedition began to stem the muddy current of the great Yang-tsze.”

* Vice-Admiral Sir James Hope (later Admiral of the Fleet) was Commander in Chief of the East Indies and China Station. He led the squadron of eleven gunboats and other vessels in the Battle of the Taku Forts that took place during the Second Opium War)

Another Blakiston in China

Fast forward 166 years, and I found myself standing on the same Bund, now a bustling promenade lined with skyscrapers and neon lights, a stark contrast to the desolate scene Thomas Wright Blakiston described. The air is thick with the hum of modern life as I gaze out over the Huangpu River. The Yangtze, it must be said, is known my a myriad of names, especially towards its end in the China Sea. The Huangpu is a tributary river that flows into the Yangtze at Shanghai. But even though I am standing in the heart of modern Shanghai, I can almost hear the echoes of the past: the clamour of workers, the distant explosions of New Year crackers, and the steady rhythm of Blakiston’s expedition as they embarked on their journey up the Yangtze.

The Shanghai of today is a classy juxtaposition of the ancient and the super-modern. Skyscrapers tower over historic buildings; golden temples hide within the confines of bustling business districts; and the once-deserted Bund is now a vibrant hub of activity. The river which once carried Blakiston’s little fleet, is now a bustling waterway filled with cargo ships, ferries, barges and pleasure boats. Yet, despite these changes, there is a timeless quality to the Yangtze/Huangpu, a sense of continuity that links my journey with that of my great uncle.

The Taiping Rebellion

In 1861, Blakiston and his chums navigated through a China in turmoil, with the Taiping Rebellion casting a long shadow over the land. His journey was one of peril and discovery, a true “boy’s own adventure” that saw him travel further up the Yangtze than any European before him.

The Taiping Rebellion, which lasted from 1850 to 1864, was one of the most devastating civil wars in history. It originated from the discontent among the Chinese population due to economic hardship, government corruption, and the influence of foreign powers. It was led by Hong Xiuquan, a schoolteacher who, after a series of mystical visions, proclaimed himself the younger brother of Jesus Christ, tasked with establishing the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace (Taiping Tianguo) on Earth. The movement advocated for radical social reforms including the abolition of private property, the division of land among the peasantry, the prohibition of foot-binding and opium, and the establishment of a unique form of Christianity.

The rebellion swiftly gained momentum, attracting millions of followers, and by 1853, the Taiping forces had captured the city of Nanjing, making it their capital and threatening the Qing Dynasty’s control. The Taiping army, characterised by its strict military discipline and its leaders’ fervent religious zeal, managed to control large portions of southern China at its peak. However, internal divisions, ineffective leadership, and the eventual intervention of Western powers alongside Qing forces led to the rebellion’s suppression. By the end of the war, the death toll was immense, with estimates ranging from 20 to 30 million dead. It profoundly affected the social, economic and political landscape of China and weakening the Qing Dynasty to such an extent that it would eventually fall a few decades later.

A boy’s own adventure

Blakiston’s expedition had been organised informally and its participants had financed the journey from their own pockets. Their reserve of cash for hiring porters, buying food and for the purchase or hire of craft in which to navigate the river, comprised Mexican silver dollars and small lumps of silver known as taels.

“Each of us carried 450 taels of silver in this form equal to about six hundred dollars,” he wrote. “And, for fear of loss from shipwreck or other mishap, we distributed the amount among our different packages. Mine was tied in old socks, and kept various company; one lot was in the next compartment of a box to my sextant; another lay snugly between two dangerous bedfellows, a bag of No. 1 shot and a tin of “Curtis and Harvey” [gunpowder]; while the remainder was distributed so as to equalise the weight of each box as nearly as possible, along with nautical almanacks, logarithm tables, flannel shirts, quinine, fish-hooks, and writing paper.”

The Victorian Lens: Blakiston’s Patrician and Dismissive Views of China

As a product of his time, Thomas Wright Blakiston viewed China and its people through a patrician, dismissive lens that had been shaped by the prevailing attitudes of the Victorian era. His writings reflect an unspoken yet pervasive sense of superiority that defined British perspectives on non-Western cultures during this period. In his account of his journey up the Yangtze, Blakiston and his companions routinely refer to the Chinese people as “Celestials” and “coolies”: terms that, while offensive by today’s standards, were ubiquitous in British discourse during that great axis era of Victorian exploration.

Masters of the world

This worldview, steeped in racial and cultural bias, reflected a time when imperialist expansion was justified by the belief in the West’s cultural and technological supremacy. For Blakiston, as for many explorers of his time, the Yangtze expedition was more than a journey into the unknown; it was a civilising mission, undertaken with an ingrained sense of Western paternalism. This sense of superiority extended not only to how he documented his interactions but also to his casual dismissal of the complexities and richness of Chinese culture. Instead, he focused on describing the perceived “exotic” qualities of the land and its people, often with a patronising tone.

While these descriptions are unpalatable today, it’s crucial to contextualise them within the Victorian mindset. These attitudes were pervasive throughout British society at that time. Viewing them from a contemporary perspective, I could clearly see the progress we have made in understanding and appreciating diverse cultures. Reading Blakiston’s writing, I found myself unable to either condemn nor excuse his attitudes. It required a balanced approach and a knowledge of British social history to conduct a nuanced examination of Victorian exploration.

If I was honest, I had held the same cynical and dismissive viewpoint myself during my first two encounters with China. But now, the veil of prejudice had suddenly lifted and I was able to clearly see, for the first time, the real China that I was now so deeply immersed in. And I was captivated.

My Personal Growth as a Traveller in China

My first visits to China in 1992 and 1994 were also coloured by a cynical and dismissive perspective. Back then, I viewed the country through a narrow lens, seeing an impoverished nation where bicycles clogged the streets, the landscape was dominated by agrarian life, and industrial progress seemed decades behind Western standards. My impressions were further clouded by Western biases, and I left China both times with little appreciation for its history, its people, or its potential.

From cynic to admirer

However, returning to China in 2024, I found myself standing in a country transformed: one that had rapidly modernised in ways I could hardly have imagined. I began to see China as more than a subject of Western stereotypes. I began to understand the depth of its history and the foresight of its technological ambitions. My early cynicism gave way to genuine admiration, not only for the country’s advanced infrastructure and technological prowess but also for its rich cultural tradition that has adapted to the modern age without losing its soul. I found myself appreciating the pace and scope of China’s growth and, surprisingly, believing in its vision for the future.

Today, I see China as offering a path forward for humanity: one that former Western powers no longer possess. It was a surprising personal transformation: a journey from prejudice to profound respect for a civilisation that now seems to stand at the forefront of the world stage, regardless of the negative ways in which it is portrayed in Western media.

Chinese Technology: From Ancient Innovation to the Digital Age

Despite often being dismissed as “backward” by Victorian explorers and traders, China has been at the forefront of technological innovation for millennia. Long before Blakiston’s time, China pioneered advancements that shaped global history.

From gunpowder to city streets

In warfare, the invention of gunpowder revolutionised military tactics across continents; in agriculture, innovations like rice terraces and sophisticated irrigation systems maximised yields to feed vast populations. Chinese engineers developed groundbreaking construction techniques, from the Great Wall to suspension bridges, and urban planning methods that created bustling, organised cities long before Western urbanisation took root. Medicine, too, flourished with traditional practices and herbal knowledge, providing a holistic view of health that is still respected and widely-practised today.

Fast forward to the present, and China has once again taken its place as a world leader in technological advancement, though now the innovations come in the form of digital systems and connectivity. The cellphone, for instance, is an indispensable device in modern China, used for virtually every aspect of daily life. From transactions and navigation to translation and commerce, the cellphone has become the ultimate tool for convenience and connectivity.

A digital Dragoman

My own journey through China brought me both surprise and delight as I discovered the full potential of this technology. My cellphone became my digital Dragoman, so to speak, as I embraced its functionalities for every aspect of my travels. Booking train tickets and hotel rooms, purchasing food and cold drinks, and arranging DiDi rides (China’s version of Uber) all became seamless tasks, performed at the tap of a finger. Even the complex language barrier — I had grossly overestimated my ability to speak and understand Mandarin Chinese — dissolved as Google Translate and the translator embedded in my Alipay app allowing me to communicate and engage more deeply with the culture around me.

As a lover and early adopter of technology, I saw the true potential of these digital systems during my visit to China. In many ways, China has made digital infrastructure an art form, with a depth and sophistication that I came to rely on in every part of my journey. When I return to China I know that technology will be my steadfast travelling companion: a modern guide through the intricate and fast-paced landscape of China. My digital dragoman will be at my side, opening doors, providing insights, and connecting me to a nation whose ancient spirit and modern innovations continue to inspire me.

The Double-Edged Sword of Digital Surveillance

Yet, while China’s technological ecosystem has revolutionised convenience and accessibility, it also carries a more complex side. In China, every move is tracked, traced, and recorded—a vast network of digital eyes ensuring a constant layer of surveillance. Cameras flash above every road, capturing images of vehicles and their drivers; every train and subway journey requires an ID card or passport for access; and, from bustling cities to the most remote villages, security cameras silently observe every inch of the country, creating a sense of omnipresent oversight. For some, this level of monitoring might feel invasive, a stark reminder of the trade-off between convenience and privacy.

For me, however, it was only a problem if I allowed it to be. Instead of discomfort, I felt a deep sense of security, finding comfort in the absence of street crime. There were no gibbering drug addicts lurking in alleyways, no graffiti defacing walls, no litter disrupting the urban landscape. Walking through the darkest of streets at any hour, I felt completely safe, shielded, in a way, by the very technology that others might find unsettling. The meticulous order of it all created a unique sense of peace, a contrast to the unpredictable edge that can linger in the shadows of Western cities. In China, I was free to immerse myself in exploration, my digital dragoman acting as both a guide and, perhaps, a guardian in a country where security and efficiency work hand in hand to shape a distinctive modern experience.

The Empire of the Spirit

China is often perceived as a land of soul-less material progress, yet beneath this veneer lies a deep and ancient well of spirituality that is once again flourishing. Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism — belief systems that have long been intertwined with Chinese culture — are now seeing a resurgence, particularly among the country’s younger generation. This rekindled spiritual interest is remarkable in a land where, for much of the 20th century, religion was dismissed as “an opiate of the masses.” Mao’s Cultural Revolution sought to suppress religious practices, tearing down temples and denouncing spiritual beliefs in a drive to reshape China as an atheistic, collectivist society. And in Thomas Wright Blakiston’s time, the Taiping Rebellion, a brutal Christian-inspired uprising, swept across the countryside with promises of reform yet left behind death and chaos, stoking further mistrust of religious fervour.

Today, however, the echoes of those violent upheavals seem a distant memory as spirituality quietly reclaims its place in the heart of Chinese culture. In my travels, I’ve been captivated by the temples I’ve visited, where incense curls into the air, monks and laypeople meditate in hushed reverence, and statues of Buddha and Confucius gaze serenely over their followers. These sacred spaces have become a testament to resilience, reflecting a profound spiritual revival that sits comfortably alongside China’s rapid technological advances.

Surprisingly, it is modern digital technology that has breathed new life into traditional worship. Temples and prayer halls now display QR codes that enable visitors to donate, pray, and pay homage with a quick scan. With a tap of their cellphones, worshippers can participate in ancient practices, bridging the spiritual with the digital. This fusion of old and new has created an unexpected, harmonious synergy, allowing China’s people to honour their cultural heritage while embracing the tools of the future. For me, this revival of China as an empire of the spirit offers a profound insight into the country’s soul, a reminder that amidst progress and change, China’s spiritual roots remain as enduring as the Yangtze itself.

Travelling With Thomas

Standing on the Bund, the very place my great uncle described in his mid-19th-century adventures, I found myself caught between two eras: the Shanghai he encountered, soaked in rain and shrouded in mystery, and the bustling metropolis it is today, alight with neon and thrumming with life. The rain that once made the city seem dismal to Blakiston still fell in torrents. But where Blakiston saw mud and squalor, I saw (and felt) the palpable energy of Shanghai, with its skyscrapers slicing the fog and the constant, dynamic motion of people and trade.

My journey in China intersected several times with this great river, and the echoes of its past — of rebellion, trade, and exploration — were constantly being blended with the sights and sounds of modern China.

Finding my way in China, tentatively at first but then with growing confidence, I came to understand that the Yangtze — indeed all China’s rivers — are like timelines, tracing the ebb and flow of history, culture and personal growth across the twin landscapes of space and time. My journey in China mirrored these waterways, sometimes rough and obscured, at other times clear and distinct, but always moving forward, shaping and being shaped by the contours of time, the land, and the life around them

Every bend and reach revealed more than just the flow of water. They told of battles fought, empires risen and fallen, and a people continually rising to meet their future, much as the river itself forever meets the sea. In this timeless cycle, both Thomas Wright Blakiston and I followed paths entwined with the river; both of us, in our way, driven by an unending quest for discovery, adventure and understanding.

Author’s Note: We will encounter Thomas Wright Blakiston later on in my journey when I visit the mausoleum of the Hongwu Emperor in Nanjing.