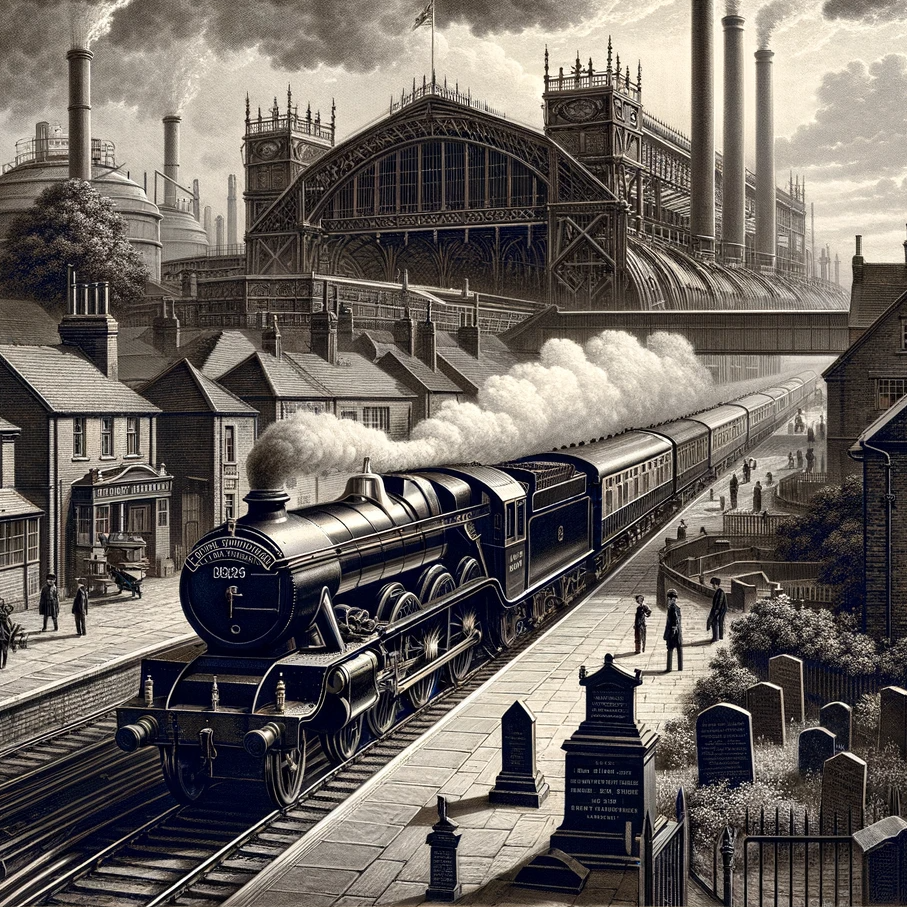

After the first powerful plain manifesto

The black statement of pistons, without more fuss

But gliding like a queen, she leaves the station.

Without bowing and with restrained unconcern

She passes the houses which humbly crowd outside,

The gasworks and at last the heavy page

Of death, printed by gravestones in the cemetery.

- The Express, Stephen Spender

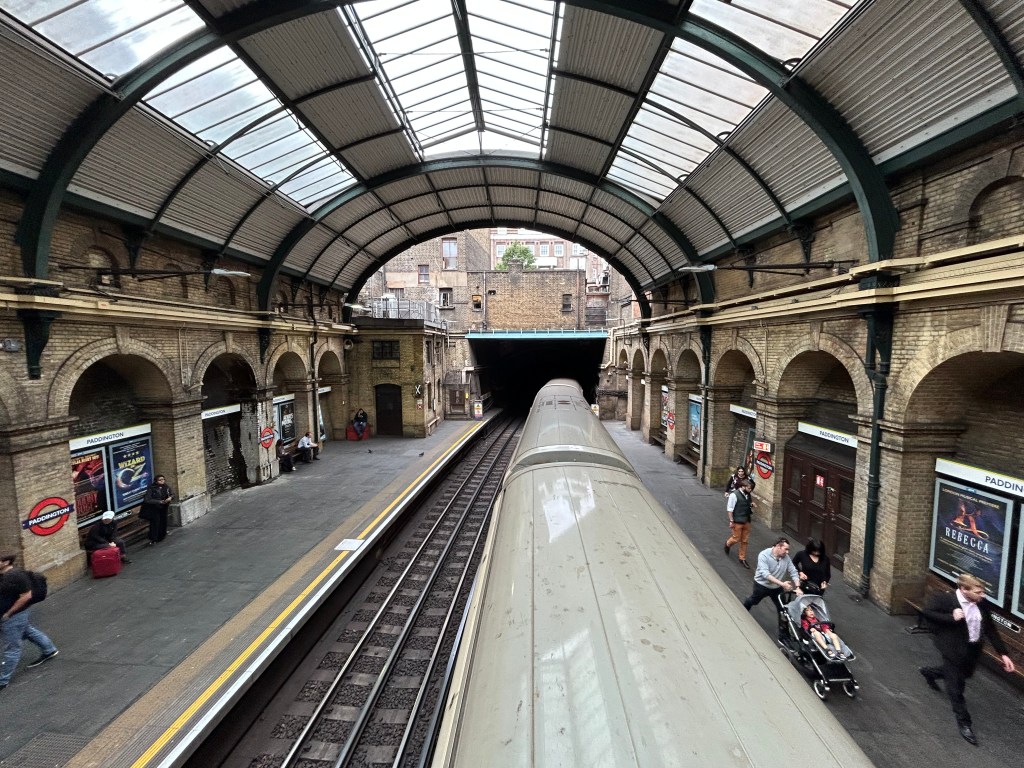

First light at Paddington Station. Six o’clock of a Tuesday morning. Staccato footsteps on the polished platforms. The sibilant hiss of sliding doors. Clipped tannoy tones intone services to Bristol, Cardiff, Swansea and Cirencester: powerful manifestos of places down the line. On Platform Seven, the GWR 6:16 service to Exeter gleams in its green and gold livery.

The station’s steel and glass roof arcs overhead: a cathedral of travel, a symphony of symmetry. Sunlight cascades through the roof’s vaulted glass. Prisms of light dance across the bustling concourse. Metallic clatter melds with the soft sough of electric engines, punctuated by the clack tack of luggage racks. Voices echo against the backdrop of this industrial ballet, as travellers weave their stories into the tapestry of the morning. And without more fuss, the six sixteen glides from the station.

Amidst this orchestrated onomatopoeic chaos, a figure sits. He is as integral to Paddington Station as the tracks that crisscross beneath its grand canopy. It is Isambard Kingdom Brunel. This titan of engineering, rendered in bronze, surveys his creation from a seat alongside Platform 4. In top hat and coattails, his presence is as commanding as the structures he envisioned. His big whiskers frame a broad, friendly face, eyes twinkling with the satisfaction of a visionary beholding his legacy. This is Paddington Station. This is his hall. And he is the railway king.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel was an engineering colossus of the Victorian age and the Industrial Revolution. Born in 1806, he is widely regarded as one of the most innovative and influential engineers of his time. Brunel’s life was a testament to relentless ingenuity and audacity.

Brunel’s early career was marked by his work on the Thames Tunnel, an unprecedented feat of engineering. Later, as Chief Engineer of the Metropolitan Railway in 1854, he was responsible for designing the railway’s tunnels, rolling stock and stations. His innovations included the use of gas lighting, hydraulic lifts and steam-powered fans to extract the soot and smoke from the line’s tunnels.

However, it was his work with the Great Western Railway that truly cemented his legacy. He designed a network of tunnels, bridges, and viaducts that, along with the broad gauge railway tracks, enhanced the efficiency and comfort of train travel. Brunel’s ambition extended to transatlantic travel as well. He built three ships – the SS Great Western, the SS Great Britain, and the SS Great Eastern, each groundbreaking in their size, power, and engineering.

Standing at just over six feet tall, with a commanding presence marked by his iconic top hat and coat, Brunel was not just an engineer but a symbol of Victorian progress and bold enterprise. His projects were characterised by innovative designs and scales that were previously unimaginable. Brunel’s contributions to civil and mechanical engineering were profound, and he remains an enduring figure of ingenuity and the transformative power of engineering. His legacy is not only in the structures he created but in the ambitious spirit he instilled in future generations of engineers.

Paddington is my favourite London railway station. While Waterloo Station is redolent of the song by The Kinks, and the gothic splendour of King’s Cross St. Pancras, evokes the vision of Valhalla in Douglas Adams’ The Long Dark Tea-time of the Soul, Paddington, for me, is the gateway to the West Country: my second home.

Leaving London from Paddington always stirs a bittersweet symphony within me. The hustle of the city, with its unending rhythm and febrile pulse, has a way of seeping into my veins. But when the train begins to roll, leaving the familiar skyline behind, I feel a gradual unclenching of my heart. The transition is almost therapeutic, a cleansing of the city’s grime and relentless pace. The urban landscape gives way to rolling hills and open fields, the sky broadens and the air seems to lighten, carrying with it the promise of peace.

Arriving in the West Country, I’m always struck by the stark contrast to London’s metropolitan sprawl. Here, time itself seems to move with a different rhythm. Its pace is dictated by the natural ebb and flow of rural life. The green and gold of the fields, the sensuous folds of the hills and vales, and the slower pace of life are a refreshing change. The air carries a mix of earth and hay. Each visit feels like a homecoming, a return to something simpler yet profoundly enriching. It’s a place where I am recalled to life, away from the glare and grind of the city.

On the other hand, I also love the feeling of returning to London, fresh from the countryside. Arriving at Paddington always brings an array of mixed emotions. The city greets me with its frenetic cacophony and dazzling lights. There’s an excitement in rejoining the fray, a sense of reconnection with the vibrant, pulsing heart of urban life.

As the train snakes back into London, an undeniable thrill courses through me. The city, with all its complexities and challenges, is a hub of endless possibilities. Its streets, alive with cultures and ideas, inspire and challenge me. The transition from the pastoral serenity of the countryside to the energy of the city is a journey of reawakening. It’s a return to a place where ambitions are fueled, where every street corner offers a new story, a new adventure.

Yet even when I am submerged in the tide race of the city, part of me still yearns for the quiet and serenity of the West Country. This duality, the love for both the city’s dynamism and the tranquillity of the countryside, is a constant tug-of-war, a balance between two worlds that both define and enrich my existence.

Despite this internal conflict, I find solace in the rhythm of these travels. Journeying to the West Country allows me to shed the layers of urban fatigue, and to reconnect with a simpler, more organic way of living that becomes lost in the city’s chaos. The West Country isn’t just a physical escape. It’s a journey back to inner peace, a reminder of life’s simplicity and nature’s unadorned beauty.

This cyclical journey between two contrasting worlds has become a vital part of my life. It is a traveller’s conundrum; a Yin and Yang balance between reflection and action, serenity and excitement. Each destination holds a piece of my heart, and together, they form a composite picture of my existence. The lush, green expanses of the West Country and the vibrant, bustling streets of London — opposing ends of the same line — each playing a crucial role in the story of my life, a melody composed of calm and chaos.

I buy a coffee and sit watching the crowds as they rush and scramble, wrapped in their lives and gone in a flash. The entrance to the Underground disgorges and swallows a stream of commuters bound for the Circle Line, the Elizabeth Line and the Bakerloo Line. Above me, the grand cast iron and glass flourishes of Brunel’s design stand juxtaposed against the sleekness of modern technology.

In my imagination, I can see two worlds: the Victorian and the digital rendered at once in black and white and shimmering colour. Digital screens displaying departure times and advertisements flash alongside the 19th-century ironwork and tiling. Amid the 21st-century hustle, echoes of the Victorian era subtly reveal themselves in the characters around me. The man in the smart suit, intently checking his iPhone, could be a Dickensian bookkeeper hurrying to his cellar-room counting house behind a wooden door with a rattle in its throat.

A woman manoeuvres a pram through the crowd. Her focus, demeanour and gentle attentiveness are reminiscent of a Victorian nanny. She navigates the teeming concourse with an air of timeless insouciance, her child cradled in its high-tech cocoon, starkly contrasting the bulky perambulators of the past.

The Aqualung vagrant, obsequiously rifling through a bin in the corner, has all the grace of a character drawn from Hard Times, Martin Chuzzelwit or Bleak House. Despite his grubby designer cast-offs — Nike trainers, North Face puffer — there is an abiding quality to his struggle. He seems to me to be a living link to the downtrodden souls who wandered the pages of Dickens, Thackery and Disraeli.

That group of teenagers crowding beneath the electronic billboard, boisterous, rowdy and demonstrative, could be the modern incarnations of the street urchins and blackguard boys that once ducked and dived through the alleys of Victorian London. Their garb is trendy and flash, their conversations filled with street slang, just as the street lads of old would shout “over ‘ere, guv’nor” and “dimber damber” at flash coves passing by.

The barista at the trendy coffee kiosk who made my oat milk latte, her tattoos and piercings an embroidery of modern self-expression, has the same diligent work ethic as a Victorian street vendor. Her swift, efficient movements echo the skilled hands of the chestnut sellers and pie merchants of the 1880s. In these vignettes, the past and the present intertwine: threads woven into the fabric of human life that stretches across the centuries.

The train standing on Platform 1 is waiting to take me to Swindon. From there, I will make my way via backtracks and B roads to the Wylye Valley. The tannoy announces boarding time. The Victorian world flickers before my eyes, fades from focus and dissolves into the bright, digital world of the present. I close my diary, leave the remains of my coffee for Aqualung, and step out into the Hall of the Railway King.