The dome of Herefordshire sky above Kilpec is so wide and blue it seems like a theatre backdrop, flecked with brushstrokes of cloud and hung with clumps of cumulus. The lane that leads to the church is quiet, save for the low humming of bees in the hedgerows and the occasional baa of a sheep from a nearby paddock. The air is still; the stillness of a hot summer afternoon in July. I let myself through the wooden gate and into the churchyard of St. Mary and St. David.

The church was built in the 12th century. It is a small, sandstone wonder, almost forgotten, hidden from the tours and tourists on their way to Tintern Abbey, Raglan Castle, Hay-on-Wye, or the Black Mountains. I’ve seen a fair few churches in my time wandering the byways of England, but Kilpeck is unexpected. Anomalous. Incongruous. In a land where saints and gargoyles dominate ecclesiastical architecture, this church’s exterior carvings seem at once heretical and pagan, yet also ashamedly alive, visceral, irreverent and transgressive.

The exterior is decorated with a chorus line of corbels, strange, carved figures that leer, grin, and grimace from beneath the eaves like the cast of some medieval carnival. There are beaked birds, wrestling beasts, knotwork dragons, and human heads wearing expressions that range from angelic to demonic. Some are obscene, others are comic, but all of them are fascinating.

I circle slowly, the crunch of my shoes loud on the gravel path in the rural silence. The most striking corbel is a wide-eyed figure pulling at its own mouth with long fingers: grotesque, unsettling, and oddly compelling. I can’t look away. The faces seem alive somehow, warmed by centuries of sunshine and softened by the patina of wind and rain. Dragons’ heads protrude from the wall, their tongues coiled like ropes. The mouths gape in varying stages of roar or exhalation: a medieval animation still flickering across the sandstone façade.

Eighty-five corbels remain, one fewer than the number recorded in 1842, and six short of the original ninety-one. They form a continuous belt beneath the edge of the roof, circling the entire building like sentinels in a strange, silent parade. No two are the same. Some come straight from a bestiary: a lion, a ram, a hound chasing a hare. One is the notorious Sheela na Gig: a grotesque female figure that has baffled and scandalised generations of visitors. Some scholars say she wards off evil. Others aren’t so sure. I just find her oddly compelling.

These carvings aren’t random. They’re the work of a group of stonemasons known as the Herefordshire School: possibly local, but influenced by the pilgrimage churches of France and Spain. Oliver de Merlimond, the steward of the local landowner, Hugh Mortimer, is thought to have brought inspiration back from the great pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela. The echoes of distant shrines and dusty European roads still cling to this quiet Herefordshire hill.

The doorway is even more elaborate. Intertwined serpents coil along the arch as I run my fingers across the stone. It feels warm and smooth, like the handle of a well-used tool. Above, a tympanum bears the figure of Christ seated beneath a canopy, flanked by two angels. They seem calm and complacent in contrast to the riotous corbels nearby. The whole entrance feels like a portal, not just into the church, but into another way of seeing the world.

One of the capitals features a green man: leafy, enigmatic, a symbol of the old forest gods perhaps, Jack-in-the-Green, or the great god Pan. On the inner left column, two warriors face off, remarkably dressed in loose trousers rather than the expected Norman mail. The arch above teems with mythical beasts: perhaps a manticore, a basilisk, dragons and birds.

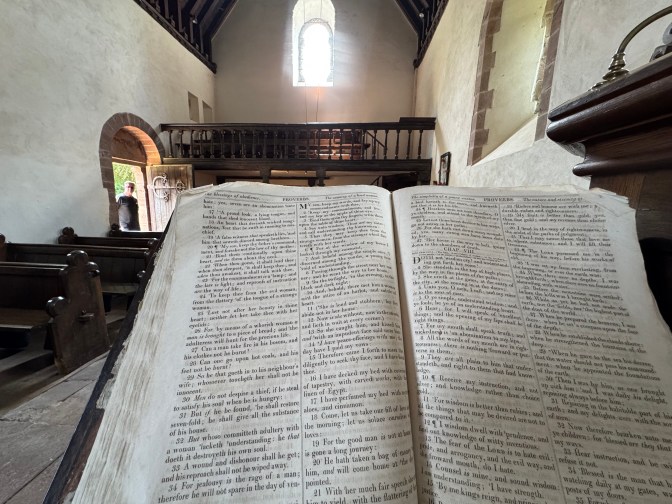

Inside, the church is cool and dim. Light filters through small windows dusted with centuries of breath and incense. The air carries a faint scent of damp stone and beeswax polish. It’s quiet, deeply quiet; the kind of silence that carries weight. I sit for a while in one of the pews, letting my eyes adjust. The Norman chancel arch, supported by squat, decorated columns, is heavy with history, like the marginalia of some illustrated manuscript.

Afterwards, I wander through the graveyard, the stones leaning like gossiping villagers. The sheep on the nearby hillside watch me with mild interest, flicking their ears and staring with the same inscrutable gaze as the corbels above. Beyond the lychgate, the ruins of Kilpeck Castle lie in a tangle of nettles and waving grass. Another flock has taken shelter in the shade of its weathered walls. One black-faced ewe looks up as I approach, as if to ask what I’m doing on her turf.

I walk around the base of the ruin. The summer heat has turned the grass brittle, crunchy, and pale. A breeze ripples across the landscape, sending waves through the sward. From this rise, the view spills out over the rolling Herefordshire countryside. It’s timeless, tranquil, greens and golds and the hazy blue of distant hills.

Kilpeck isn’t on the way to anywhere. You have to seek it out. But in doing so, you find a place where time bends just slightly and the faces of the past peer out from the stone, forever caught mid-grin or grimace. I walk back to the car, the faces of dragons and green men following me in silence.

bloody good yarn -like all the rest

LikeLike